Finding and catching American shad in New England’s largest rivers.

The American shad has long been an iconic fish along the eastern seaboard and an important staple in the lives of New England anglers, both past and present. While these anadromous fish live most of their lives in the Atlantic Ocean, every spring, adult shad return to large freshwater river systems to spawn the next generation of their progeny.

Ever since the last glaciers retreated, people living along our major river systems have relied on the spring runs of American shad, along with alewives, striped bass and other anadromous fish, as a source of food and economic importance. Significant evidence shows indigenous and native people took advantage of the prolific runs of shad for millennia. By preserving their meat through smoking and drying, springtime hauls of shad provided year-round sustenance and were valuable in trade. The most effective tool in catching shad were rock weirs or obstructions that channeled fish into narrow passages where they could be netted or speared. Some of these stone structures still exist in our major rivers today.

This practice of shad fishing and preservation for food and commercial purposes was copied by settlers and colonists. “Shad shacks” have long persisted on the banks of the Connecticut River. Still today, commercial anglers seasonally net and sell shad to various fish mongers and markets. Boned, or fresh shad, smoked shad and shad roe (egg sacks) are considered a seasonal delicacy in the region. In fact, the American shad was designated as Connecticut’s state fish in 2003 due to their great historical significance.

With a range from Newfoundland to Florida, American shad used to run up numerous tidal rivers along the East Coast. However, with industrialization and dams came the extirpation of shad from much of their historic habitat. The Connecticut River still stands as one of the largest and most reliable shad runs in the region. While greatly reduced from its peak numbers, the existing “Connecticut River American shad population is considered stable” according to a stock assessment conducted by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission in 2007. Great efforts have been made by fisheries divisions in Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont and New Hampshire to restore American shad to their historic homes over the last 20-plus years.

What does all this historic significance mean for today’s recreational anglers? Well, loads of light-tackle fun of course. Shad are a blast to tangle with when targeted on light tackle. The timing of the shad run is also a sort of celebration of spring and the return of migratory fish to our waters before some of the more popular fish like striped bass and fluke return. There is also something unique about targeting and taming a fish that normally dwells in the harsh conditions of the ocean on an inland waterway as they make their migration.

Where To Look

When shad enter our major river systems they are on the move. They move in from the saltwater, through the brackish zone and head north toward spawning habitat and tributaries of the main river system. They don’t make this journey all at once and, once they are in the river, they wait for opportune times to spawn before heading back downstream and out to sea. Often, shad will pause on their journey upstream to spawn in natural current breaks in what can be considered ‘holding water’.

Examples of holding water can be naturally occurring features like deep channel edges, the outside of back eddies and on seams created by points or natural obstructions. Most often though, shad can be found holding near manmade features such as the lee of bridges, along deep cuts near walls, deep-water docks or jammed up against non-natural obstructions like dams. Many popular shad spots combine ease of access and some mix of these features.

When you do find a popular shad spot, you are unlikely to be alone. Shad fishing is often a communal experience and the best locations are often “shoulder to shoulder” on a nice day during the peak of the run. This is a big part of the celebratory nature of welcoming the return of the shad and the spring season in general. The hooting and hollering as anglers hook up throughout the line with acrobatic shad taking to the air is as much a part of the experience as actually catching the fish. The communal nature of shad fishing as both fish and anglers gather in concert harkens back to what it must have been like when native people and fish converged during short windows of immense opportunity. One can only imagine there must have been some sense of celebration to that period of springtime renewal and revival as well.

If you are new to shad fishing, your best bet to shorten the learning curve is to head to your local tackle shop and spend a few dollars on the terminal tackle to get you in the game. You’ll likely get a few tips on where you might get started in targeting shad as the popular areas are often a poorly kept secret.

Match Your Tackle

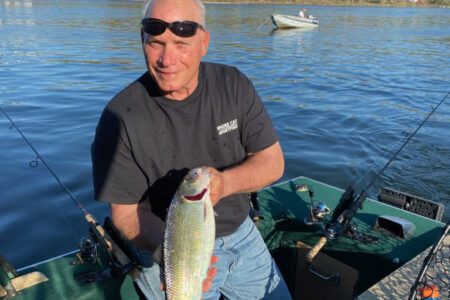

Rod and reel shad fishing is generally considered a light-tackle endeavor. Their average size is 3 to 4 pounds with a 5-pounder considered large. A quick look at the Windsor, Connecticut Shad Derby winners from the last 15 years confirms this with a fish of somewhere in the vicinity of 5 pounds usually takes first place. The smaller males, known as “bucks”, are usually in the 2- to 3-pound range with the heftier females, commonly called “roe” running larger.

Although they aren’t huge, returning adult shad have had to survive a life out in the ocean. They pull hard and are known for their acrobatics. Combine these traits with their paper thin, “soft” mouths and you’ll need tackle light enough to delicately play these spirited fighters to the net.

Most anglers choose a light action rod somewhere in the 6- to 7-1/2-foot range. Rods in this length rated for 4- to 10-pound line give an angler the ability to accurately cast at a distance and enough backbone with a soft tip not to pull the hook on a feisty shad. These rods are most often paired with reels in the 2000 to 3000 size and a smooth drag is a plus. In recent years, many shad anglers have converted their main lines to ultra-thin braid in the 10-pound range; this allows for longer casts, a faster sink rate and a more effective drift.

Getting Bit

Shad can be caught with a variety of rigs, but there are two that stand out here in southern New England, especially along the Connecticut River and its tributaries. The shad dart and the willow leaf are by far the most popular shad lures along the lower stretches of New England’s longest river. Out of these two presentations, the willow leaf tends to be the more versatile and widely used, with the darts being most effective in fast, shallow water.

Regardless of lure choice, it is important to present it where the shad are most likely to be – within a few feet of bottom. It is helpful to keep in mind that these fish are not in the river to eat. Their primary concern is successful reproduction, but like many other migratory spawning fish, they can be tricked into biting a pesky artificial lure. To get a shad to snap you are trying to achieve a natural drift, bouncing along bottom – think trout fishing with a worm and sinker, or bouncing bucktails in current. Casting across current and tinkering with your drift by quartering up or downstream according to the speed of the current and your proximity to the structure you’re fishing is an effective way to locate fish. As with many other forms of deep drift fishing, if you aren’t losing rigs, you probably aren’t staying in the strike zone for very long.

As willow leaves are not naturally heavy, most anglers use an inline drail weight to aid them in getting their offering down to bottom. A very general shad rig consists of the mainline tied to one end of the drail. Keeping a variety of weights on hand is a good idea as the amount of weight needed to get you down into the strike zone can vary greatly from spot to spot and based on river conditions, from day to day. My shad box contains weights ranging between 1/2 to 1-1/2 ounces. A 5- to 6-foot fluorocarbon leader of 6- to 10-pound test connects the other end of the drail to the willow leaf, depending on current and water conditions. For example, if you’re fishing in shallow clear water you might err on the lighter side, but when fishing deeper, murkier and more snag-prone areas, the heavier line gives you a better chance at staying connected to your lure and the fish. The ultimate goal is to have your leaf fluttering in the current, out ahead of your weight within a few feet of bottom.

Willow leaves come in a wide range of colors and finishes; local shops sell them and others might be sold out of the trunk of a fellow angler’s vehicle. As in most things related to fishing, color tends to be a hotly debated topic. Leaves come in gold, copper and silver, with hammered or smooth finishes. Many of the leaves that are sold are then custom painted with various colors of paints through a variety of techniques. The latest rage in in leaves is UV finish. My take on all this is that the actual color of your leaf, or lure doesn’t matter much. The base colors, gold, silver etc. can make a difference sometimes based on light and water conditions. Beyond that it doesn’t make much difference as long as you’re consistently keeping your lure in front of fish. All of that said, I’d hate to be the only angler on the bank without a pink leaf in my box when that is the only color catching fish!

Somehow, the color of shad darts is a much less contested subject. Shad darts are deployed in a similar fashion to leaves in that they are bounced along bottom. The difference in their presentation is that the weight is part of the lure itself. Shad darts are most commonly used in areas of heavy current, in riffles and pocket water, especially below dams.

Endgame

You are allowed to keep six shad per day, per Connecticut regulations and three per day in Massachusetts. Some folks wait all year to eat shad and their roe while others give them away; many others practice catch and release. Regardless of your intention for your catch, one thing that most shad anglers have in common is the use of a long-handled net to subdue these fish at the end of the fight. Most shad are lost at the riverbank. There are a few reasons for this. First and foremost, if you intend to land your catch, the fish has fought for some time and the longer the fight goes on, the more likely the fish is to spit the hook; this is due to the softness of their mouths. Also, if you intend to release your catch, a soft, long-handled net goes a long way in protecting them. Though they are hardy, shad easily shed their scales that keep them protected.

Fishing for shad is a great way to get out and celebrate the return of spring, as people who have lived in New England have done for thousands of years. This year, get out and join the party at the river bank and have your own celebration with a cartwheeling shad on the end of your line.