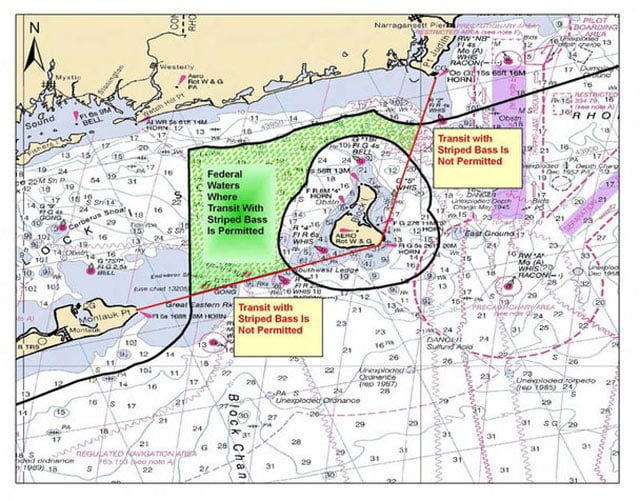

A view from both sides on the debate of whether or not to open the transit zone between Montauk Point and Block Island, and between Block Island and Point Judith.

FOR

By Capt. Joe McBride, Legislative Representative, MBCA

The Montauk Boatmen and Captains Association (MBCA) supports the opening of the Transit Zone to recreational fishing for the following reasons:

- This approximately 10×15-mile area is an anomaly since it is the only East Coastal area to have this restriction on its historical bass fishing geography. The rest of the coast is constrained to the three mile limit of each state. The only exception is Cape Cod Bay, which has an approximate 10-mile state area in order to protect their recreational fisheries.

- At a Congressional hearing, a critic of the reopening stated that the Transit Zone was a striped bass breeding area similar to the Chesapeake Bay and other regions. At the hearing, I responded that the Transit Zone was just an area that striped bass moved north through in the spring and returned south through in the fall. Some pods of striped bass do remain in the area during the summer months.

- The area comprises over 60 percent of New York’s and Rhode Island’s historical striped bass fishing areas. Restoration will distribute the fishing efforts over a greater area rather than have hundreds of boats confined to a small area, which is what happens now.

- Striped bass size and bag limits are set by New York State and the ASMFC. This reopening will not increase the catch, even with the redistributed effort.

- Recreational anglers did not cause the abuses of the fishery that resulted in the restrictions placed on the fishery.

- Since data is so important to the establishment of regulations, we respectfully request any data that reveals how the opening of the Transit Zone might result in compromising the health of the striped bass fishery.

OPPOSED

By Charley Soares – As it appeared in RI Saltwater Anglers Association (RISAA) Newsletter

“Just because almost everyone fishes there and most of them are getting away with it doesn’t make it right.” That is just one of the predominant sentiments I have been privy to regarding the EEZ, and the federal waters at Southwest Ledge off Block Island. The more virulent comments I will leave to your imagination because when the topic is striped bass, emotions, pro and con, run high. When I was serving on the Marine Fisheries Commission during the rebuilding years of the striped bass moratorium there was this inside joke. Two stripers of breeding age had been located and a multitude of anglers were lined up back to back and elbow to elbow competing for a permit to kill the last one. Gratefully we aren’t down to just two stripers but anyone who believes the striped bass stock is healthy has not been fishing or listening to concerned fishermen all along from New England to New Jersey. The late, great Bob Pond was one of the stripers’ most ardent advocates and a perceptive individual who predicted the precipitous decline of stripers during the late 1970s into the early 1980s when the stock crashed and a moratorium was imposed.

The moratorium worked but not just because of the sacrifices of anglers but good old-fashioned luck. Stripers spawn in much less than ideal conditions and listening to men like Pond, John Cole, and the insightful and hardworking watermen of Chesapeake Bay that contributed to their first-hand experience of spawning success has been proof of that. Pond, Avis Boyd and most of those men took a month out of their lives, on their own dime and helped net, then strip eggs from swollen females and milt from males to ensure that nature didn’t have the last word. Here is a passage from Cole’s 1978 classic, STRIPER, a story of fish and man in which he recounts the following. “The fish move with the phases of the moon, the times of the tides, the warming of the waters. They move in response to migratory mysteries yet unsolved, yet unknown. The larger females, ponderous with their ripening eggs, bull past or through the gill nets of Maryland watermen who watch each April for the coming of these silver creatures they call ‘rock.’ They clog the river passage with the suspended tendrils of meshes hung in a lacework from one cork line to another. The nets collect their tolls. The bass for whom the river is a passage toward the preservation of the species, come sliding, silver, over the gunwales of the skiffs. Some but not all. Even as the twine is raised and tangled fish retrieved, more stripers swim beneath the watermen in a living countercurrent that cannot be turned.

As long as a tall man’s leg with black/green backs, sides stitch from gills to tail with seven dusky stripes, and bulging bellies as silver bass white as the new moon, some of these brood females, these supple cows will cast more than a million eggs. Their body cavities swell with their burden….a thousand creatures each laying 600,000 eggs, if, as is also ordinary each of the thousand females is tended by three mature, milt heavy males, the release of semen and eggs in a few acres of this narrow river can alter the river itself. This spawning turmoil is what the waterman call a Rock fight. Even as the parents depart, spent now, riding the river current to the sea, within three days while millions of its brethren have died unborn within the small universe of their chorion (egg sack), this cell group becomes the larva – a distorted miniature of the great stripers that spawned it. It is one of 600 of the 600,000 eggs released by his maternal parent. When two Aprils have passed, the eggs of this morning on the Nanticoke will have grown to a foot long, their histories are sagas of survival. Nourished by the struggle, as well as by their constant consumption of protein, the second-year stripers, (on the brink of adulthood) have compressed a vitality within their skins that surpasses the extraordinary.

These are the questions to ponder as the only three 2-year-old stripers, the legacy of 600,000, prepare to leave the Chesapeake. Moved, perhaps by the compulsion of their own vital spirits, or perhaps by the drumming of the need to migrate, these fish, this year, will join their parents when April ends and more abandoned eggs cloud the Nanticoke. Riding the river currents to the sea, they will travel south to Cape Charles, where the bay meets the open ocean. From there, the stripers will turn north, creatures of the wild Atlantic now, embarking on an adventure which began on an April night more than 50 miles north in the Nanticoke’s milky swirls of milt.”

It took little more than the amazing prose of John Cole to convince this fisherman that each striped bass is a miracle. This writer has held a commercial fishing ticket since I began selling 16-inch stripers when that size was the only restriction on a species, known then as Roccus. On most occasions I still take my daily creel limit of one striper to feed old friends and those who would not otherwise experience the delicacy of fresh fish. I have fished Block Island all my life and never once felt the need to fish more than a mile from those productive rocky shores. We have an opportunity, in a coalition of man and nature, to preserve and conceivably increase the female Spawning Stock Biomass (SSB) but opening up the EEZ to striper fishing is certainly not a means to that end. We must insist that these great fish be allowed to summer in those waters free from harassment by hook and net to become the parents of the most important species that swims in our waters. We need concerted law enforcement and penalties that result in more than a slap on the wrist. Take away the licenses and permits as well as all the valuable equipment of those who break the law and deposit those returns into a dedicated enforcement fund. That will end or severely diminish the plundering of stripers in that area.

There is also the risk that opening the EEZ around Block Island will lead to the relaxing of EEZ restrictions in other areas, such as the waters off of North Carolina and Virginia where large numbers of big female stripers spend their winters, and where fishermen from those states have been lobbying for access to those fish for years.

I am extremely grateful to Bob Pond and John Cole for their friendship and the dedicated men and women who are working the natal rivers of our precious striped bass in an effort to save these great fish for the future of all who share a reverence for these magnificent seven-striped fish.