The concept of anglers releasing fish as a conservation measure has its roots in the early days of American fly fishing.

For example, Thaddeus Norris, considered by many as the father of American fly fishing, expressed concerns about the destruction of our fisheries in his 1864 The American Angler’s Book and called attention to the need for resource conservation, remarking that he released as many fish as he kept.

In Adventures in the Wilderness published in 1869, William Henry Harrison Murray, also known as Adirondack Murray due to his efforts to introduce city dwellers to the rewards of camping and fishing in the Adirondack wilderness, urged anglers to restrict their harvest of fish to “that which is needed for food” noting that he typically released half of his day’s catch.

Prominent outdoor writer George Parker Holden, who is credited with starting the home rod building movement among American fly fishermen, professed that anglers should not be afraid to join the slowly growing fraternity of individuals whose motto is “we put ‘em back alive!” in his 1919 book entitled Streamcraft.

Gifford Pinchot, who served as the first Chief of the US Forestry Service and is considered to be the father of American forestry conservation, published Just Fishing Talk in 1936, noting that “we love the search for fish and the finding, the tense eagerness before the strike and the tenser excitement afterward; the long hard fight, searching the heart, testing the body and soul; and the supreme moment when the glorious creature, fresh risen from the depths of the sea, floats to your hand and then, the hook removed, sinks with a gentle motion back from whence it came, to live and fight another day.”

Perhaps the most well-known early advocate of catch-and-release was fly fishing pioneer Lee Wulff. Considered by many to be the father of catch-and-release angling, Wulff’s 1939 Handbook of Freshwater Fishing included his now famous declarations that “gamefish are too valuable to be caught only once” and “the fish you release today is your gift to another angler and remember it may have been someone’s similar gift to you.”

Catch-and-release has continued to grow in popularity as a conservation ethic among recreational fishermen; however, despite the best intentions of anglers practicing catch and release, poor fish handling practices can have a negative impact on individual fish. And, while it’s easy to assume that all of the fish you release survive unscathed since they appear relatively unharmed when landed and readily swim away when released, studies have documented that in virtually all cases some proportion of released fish later succumb to the effects of physical injury or physiological stress caused by angling, while others experience sublethal effects that can include a compromised ability to fight off diseases and parasites and heal wounds caused by hooks, alterations from normal behavior such as disruption of feeding patterns, a loss of equilibrium and impaired swimming performance and increased vulnerability to attack from predators.

Stress Factors

Angled fish can experience physiological stress and injury for a variety of reasons. Physiological stress begins to occur in fish due to ‘burst’ exercise when they are hooked and attempt to avoid capture. Then, if they struggle intensely for prolonged periods during the fight they become exhausted. When angled to exhaustion, lactic acid builds up in their muscle tissue leading to a situation known as acidosis. Acidosis, in turn, leads to physiological imbalance and muscle failure.

Terminal tackle type, including the number and style of hooks and type of bait or lure used are all factors that can affect the location where a fish is hooked and the likelihood of physical injury to organs and tissue from hook wounds. In general, being hooked in sensitive locations such as the gills, eyes, throat, or stomach increases the risk of injury during angling as well as when hooks are removed.

The manner in which fish are landed and handled prior to release can cause additional injuries and lead to a cascade of other physiological changes such as depletion of energy stores, increased heart rate, and release of the hormone cortisol which can lead to suppression of the fish’s immune system making it more susceptible to disease. In particular, keeping fish out of the water during catch-and-release, even for short durations, can compound the physiological disturbances experienced during angling especially if the fish is exhausted from a prolonged fight or injured during hook-up or landing.

How Fish Respire

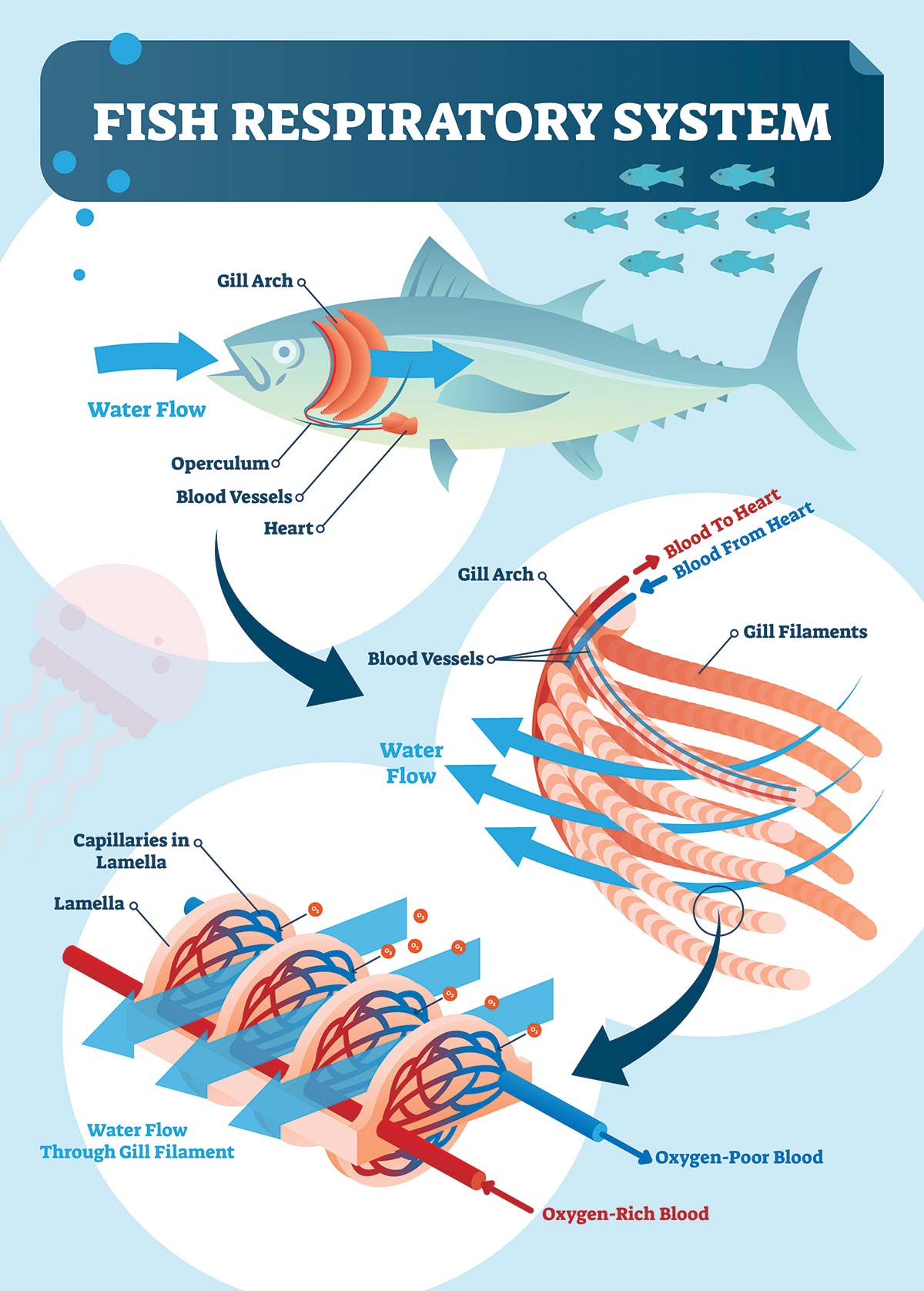

Let’s briefly examine how fish breathe. Fish “respire” by moving large volumes of water through their mouth and over their gills. Gills are made up of feathery structures called gill filaments which provide a large surface area for exchange of gases. The gill filaments are organized in rows in the gill arch. Each filament is comprised of tiny, delicate structures known as lamellae, which are discs supplied with capillaries. Blood moves in and out of the gills through these small blood vessels. Water flowing across the lamellae is essential for proper functioning for fish to breathe. When water moves over the gill filaments, the blood within the capillary network takes up the dissolved oxygen from the water and the circulatory system supplies oxygen to all of the tissues of the body.

Air exposure occurs once an already exercised fish is landed and removed from the water to be unhooked, measured or weighed and, in many cases, admired and photographed. Once out of the water, gill filaments adhere to one another, the gill lamellae collapse, and gas exchange normally occurring via the capillaries in the gill lamellae stops, halting respiration. This results in the fish experiencing an oxygen debt, cardiovascular alterations, and an accumulation of additional metabolites that decrease blood pH and combine with the lactic acid released while fighting the fish increasing extracellular acidosis. As previously noted, this leads to physiological imbalance and muscle failure, which jeopardizes their post-release well-being and survival.

In addition, air exposure can cause the fish’s skin to begin to dry out and become damaged, especially if the fish is held with dry hands, dragged across the dry sand, or handled in another manner that removes the fish’s protective mucous (slime) layer. Damage to the skin and slime layer make the fish more vulnerable to disease and parasites.

So, even if not lethal, injury and stress experienced during angling combined with air exposure once a fish is landed have the potential to lead to behavioral alterations and fitness impairments as well as compromise their ability to cope with environmental stressors after they are released.

Air & Environmental Stressors

A number of studies have documented the fact that stress and stress-related impairments experienced by fish caught and released is temperature dependent. For example, most species are better equipped to handle periods of air exposure at cooler water temperatures and warmer water can interact with air exposure to prolong post-release recovery times or even potentially negatively impact their survival. Therefore, the closer the water temperature is to the upper end of a species thermal tolerance range, the more important it is to minimize air exposure.

Air temperature when a fish is caught and released is also an important environmental factor to consider. Any abrupt or substantial temperature increase experienced when a fish is removed from the water, even for a brief period of time, can add stress. This is especially important during hot weather, when there are large differences between water and air temperatures.

In some cases, when water temperature rises to extremes or the air/water differential is substantial it may be best to simply cease targeting a particular species until temperatures moderate.

A fish’s life stage may also have an impact on fitness and survival of air exposed fish. Research suggests that larger individuals of many species may be more sensitive to angling stressors due to a combination of increased energy needs and their strong swimming abilities that often result in longer fight times making them more vulnerable to stress and injury at more minimal periods of air exposure.

Minimizing Impacts Of Air Exposure

The bottom line is that air exposure doesn’t benefit fish and the longer a fish is out of the water the greater the potential negative impacts. Certainly, the simplest recommendation is that anglers should strive to reduce the amount of air exposure for fish they intend to release and whenever possible, avoid taking fish destined for release out of water.

This can be accomplished by employing the following tools and techniques:

- Use appropriate weight-class tackle with properly set drags that allow you to bring fish in quickly to reduce exhaustion and minimize stress.

- Replace treble hooks with single hooks and crimp or flatten the barbs on hooks to make it easier and faster to remove them.

- Once a fish is hooked, land it quickly rather than playing it to exhaustion. A fish brought to shore quickly has a much better chance of survival after release than one that has been exhausted by a lengthy fight.

- Once landed, fish should be unhooked quickly and carefully in the water whenever possible.

If a fish must be removed from the water to unhook it, a recent review of studies on air exposure thresholds published in the American Fisheries Society journal Fisheries affirmed that even short durations of air exposure can be harmful to fish intended to be released, recommending that limiting air exposure to 10 seconds or less is best for most species. As the authors note, limiting air exposure to 10 seconds is a relatively simple and safe guideline that still provides sufficient time for anglers to admire, measure, and photograph their catch without causing significant harm during catch-and-release.

| LEARN MORE |

| For a summary review of the literature regarding air exposure thresholds see the article by K. Cook, R. Lennox, S. Hinch and S. Cooke entitled Fish Out of Water: How Much Air Is Too Much? published in Fisheries, Volume 40, Number 9 (September 2015).

For a summary of angling tools and tactics that can be employed to minimize impacts of catch-and-release angling on fish see the article by J. Brownscombe, A. Danylchuk, J. Chapman, L Gutowsky and S. Cooke entitled Best Practices for Catch-and-Release Recreational Fisheries – Angling Tools and Tactics published in Fisheries Research, Volume 186 (2017). For additional information on science-based practices to catch, handle, and release fish in a manner that ensures that they are likely to survive and thrive visit Keep Fish Wet at keepfishwet.org. |

Finally, while fish in good condition should be quickly and gently returned to the water head first in an upright position, fish that appear exhausted, stressed or injured should be revived prior to release. Always revive fish by holding them headfirst into the current or direction of the seas in the swimming position with one hand under the tail and the other under the fish’s belly or grasping its jaw between your thumb and forefinger. It is important to always move the fish gently forward or in a figure-eight pattern to get water flowing through the mouth and over the gills.

Never move the fish back and forth or backwards. Do not let the fish go until it clamps down on your thumb or is able to swim strongly and freely out of your grasp on its own.

As anglers, it’s all about the choices we make as we control of the many factors that can stress or injure fish that are caught and intended to be released. Adding proper catch-and-release techniques to your fishing arsenal will reduce stress, minimize injury, and increase the chances of survival of fish that you release.

John Tiedemann is Assistant Dean in the School of Science at Monmouth University and Director of the University’s Marine and Environmental Biology and Policy Program. His work over the past 40 years in the classroom and the coastal community has addressed a wide range of marine and environmental science and natural resource management issues in the region, including the launch of the angler-based research and education campaign Stripers for the Future.