The next big invasive species that regulators want you to catch, kill and eat!

As with the iconic Bob Dylan track, life is full of surprises, some expected. And so it goes with the continual influx of invasive species. This time it’s the blue catfish, not far behind the tail fin swipes of the flathead forerunner.

Later than sooner, but it’s only a matter of time. If migration (read: invasion) is at the pace of its flathead kin, better go with the latter time frame.

Welcome the perhaps not so welcome blue catfish to the Delaware River up to the Trenton area, and likely in some of the lower river’s tidal tributaries, most likely the Oldman’s, Alloway, Big Timber, Mantua, and Raccoon creeks, possibly up to the Rancocas Creek. The Maurice River is another swim of a more likely than not blue colonization. The blue is joining the ranks of the Garden State’s whiskered clan that includes the channel, flathead, white catfish, and the brown bullhead.

The true behemoth of group, the blue catfish is capable of attaining weights in excess of 100 pounds. The Virginia state record caught in 2011 pulled the hash to the eye-popping 143 pounds. Maryland’s top mark is a whopping 104 pounds. Delaware’s biggest blue registered at 48 pounds, 3 ounces. A kitten, so to speak, but no doubt there are much bigger blues prowling the First State’s brackish tidal flows.

Originally a denizen of the Ohio, Mississippi, and Missouri river systems, the blue catfish has been stocked in lakes and impoundments as far west as California with stunning success, especially if big fish pleasure is the measure. Its range is north to Minnesota. However, via stockings into Virginia’s Rappahannock and James rivers from 1973-1977 to increase recreational fishing opportunities, and then via migration into all major Virginia tributaries of the sprawling Chesapeake Bay and then into Maryland swims, namely the Potomac River spread, Big Blue is now firmly entrenched as a Mid-Atlantic fresh and brackish water resident.

And its trek northward is already underway.

Year Of The Cat

As the adage proclaims, “The path to hell is paved with good intentions”, and the species is stark evidence of that, although “fisheries hell” is more apropos. How so? As with the flathead, it is an eating machine, plain and simple, and has the same urge to travel, i.e. naturally wired to expand its range.

“Fish have fins,” as one fisheries biologist quipped.

However, far more so than the flathead, channel and white, the blue can take higher doses of saltwater, thus enabling it to enter, reside and traverse tidal environs that would blunt other catfish intrusions. This wasn’t expected, and within a few years it was out in Chesapeake Bay and finding its way up some of the tributaries on the eastern and western sides, most likely establishing spawning populations there.

Far more alarming was the appetite and consumption factors. There was little, if anything the species would not inhale. It developed a taste for blue crabs, clams and oysters, herring, bunker, shad, small stripers, white perch, and most other finned critters, even eels; you name it, they ate, and are eating it right now! It’s the impact on the blue crab that is of sharp concern. It was estimated in a study by the Virginia Institute of Marine Science that blues glom in excess of 2 million juvenile blue claws a year, and that’s only in the lower reaches of the James River alone. One can only imagine the huge dents being made elsewhere.

Conflict was bound to happen in a big way as per the concern over the impact that swarms of blue cats might be having on the respective environments and particularly the commercial fishing sector. In 2023 Maryland Governor Wes Moore fired off a letter to the U.S. Commerce Secretary citing the possible damages invasive species like the blue cat and also the flathead and northern snakehead could be causing in the Chesapeake Bay system.

Prior, in 2012, a Bay Program Invasive Catfish Task Force was formed to share information between agencies in the watershed insofar as blue and flathead intrusions and work to formulate a response strategy to the species expansion.

Be Your Sledgehammer

From a recreational fishing standpoint, though, what’s not to like about the blue catfish? It’s certainly adaptive and can be caught in a variety of venues. The kitty gets big, that’s for sure. And like the flathead, and to a lesser extent the white amur (grass) carp and pure strain muskie, it’s as close to big game fishing as one can get in freshwater, or in the case of the blue, brackish water. It strikes both live baits and chunks, and is known to whack lures. While we’ve never had the opportunity to enjoy fried or broiled blue kitty fillets, fish cakes or chowder, a few we’ve spoken with who have partaken of the aforementioned entrees give it higher marks than the channel or flathead meat.

What’s not to like? The sledgehammer strike it can have on an ecosystem, from its voracious eat-it-all appetite to crowding and possibly eliminating established species. In other words, they will wreak havoc on an ecosystem if left uncontrolled. The million-dollar question is “Can the blue be controlled, and if so, to what degree?”

Chris Smith, a principal fisheries biologist with New Jersey’s Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) Bureau of Freshwater Fisheries, and member of an invasive species study group, opined that the blue migrants most likely moved through the 14-mile Chesapeake and Delaware Canal and entered the Delaware River proper just south of Wilmington before spreading up and down. There’s no way to pinpoint when the fish entered what is considered Garden State waters, but in 2020 he received an image of what Smith verified as a blue catfish caught in Lower Alloway Creek, a tributary of the Delaware. That the species eventually made its way into New Jersey was no surprise given its proclivity to travel and higher tolerance of saltier water.

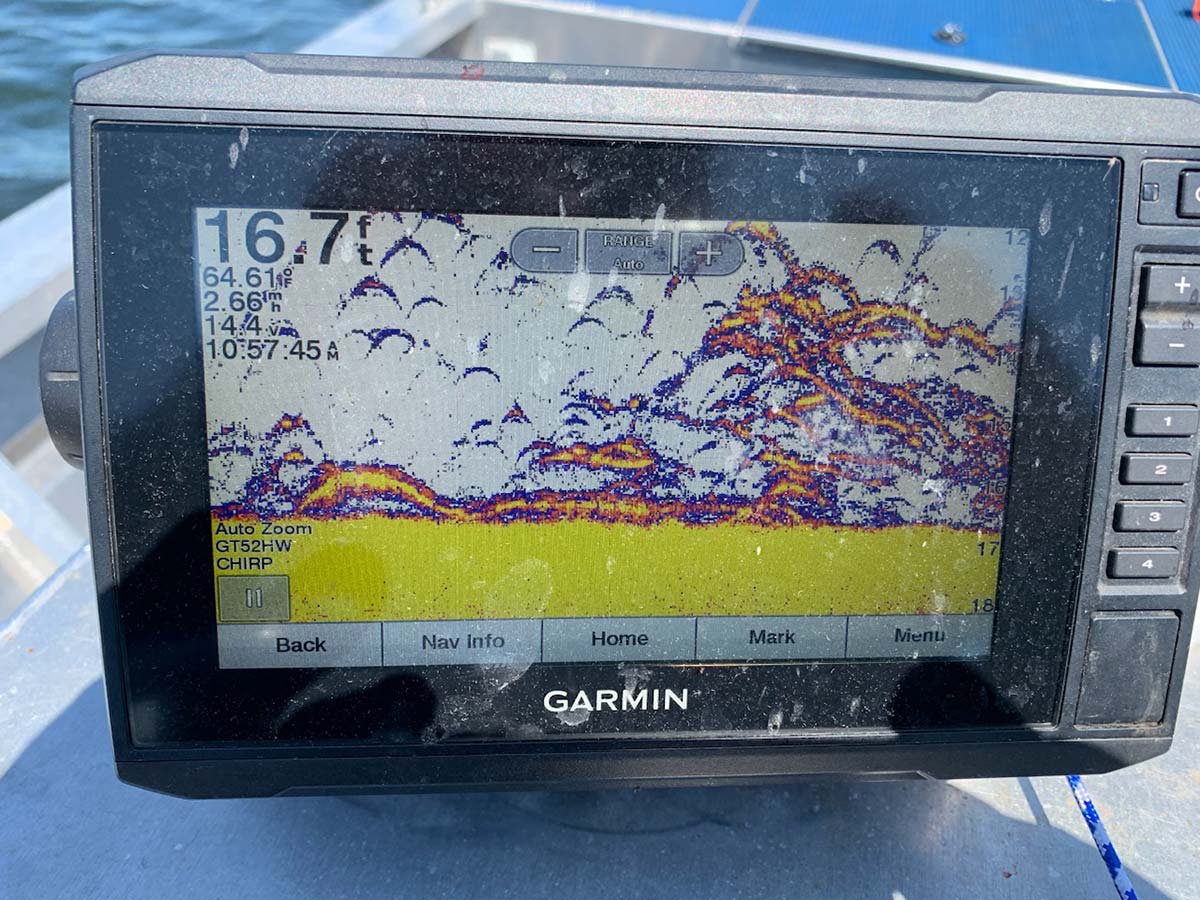

Having seen the image, there was no doubt that blues would be in the river proper. That was brought to a nodding, smiling light while on a shad sortie this past Easter morning with Capt. Dom Troisi from Full Draw Bowfishing on the Delaware, about a half mile or so below the Calhoun Street Bridge. Anchored and doing the catch and release thing, while dodging jumping sturgeon and gaping at the amount of surface rolling stripers, he showed me a photo of double-digit weight blue cat caught the previous autumn in a spot a few minutes downriver from where we were dead sticking. I know my kitties, and this was a blue for sure, not a channel. “Yeah, they’re here,” he shrugged, pointing to his electronics screen that showed more wavy multi-colored lines than on my melon.

“These are stripers, these are channel cats and maybe flatheads, and these, down here, might be blues,” he said while pointing to the screen, adding “A guess, but probable.”

As sturgeon jumped and rolled around the boat. Based on fishing success, I’ll bet on Capt. Dom’s supposition.

Dead Or Alive

Closely resembling the channel cat – including the forked tail – the new blue neighbor is identified by its squarish anal fin that sports 30 to 35 rays; the channel has 24 to 29. Spots are not a reliable indicator, as bigger channels tend to lose these. Both are a bluish/silver to bluish/black in coloration. Yeah, count the rays to be sure. Here’s the stick as the blue, with no minimum length and/or possession limit like the channel, becomes more prevalent.

Blue cats prefer slightly swifter water than the channel and flathead, and tend to hang at the tail end of deeper pools rather than the belly rubbing bottom. And there’s nothing a blue won’t consume, even if a fight might be involved. Stomach survey studies have found that in addition to soft and spiny ray fish, the likes of muskrats, snakes, songbirds and ducklings have been ingested, and no doubt there have been mice, rats and buster bullfrogs going down the gut.

Tactically speaking, bait is the tried and true method for tackling blue catfish, both stationary and live. These cats are opportunistic feeders to the nth degree that will grab anything that tickles not only its barbel feelers but all the catfish clan’s sensory spot taste buds deem as prospective prey, including the struggles of a livelined shiner, palm length sucker or chub, sunfish, crayfish or frog. Certainly not to be overlooked are the still baits, such as chicken livers, cuts of shad, Atlantic herring and/or bunker and false albacore.

Yeah, a taste for everything live and otherwise and a middle ground between its two bigger kin, the flathead a 99.9% live offering crusher, and the channel (and white as well), a 50-50 chomper of either. Circle hooks? Only if you prefer to let the hook do the hookset; in terms of health catch and release, these fish, upon capture, must be killed. In fact, you might want to visit a few of the coastal tackle shops stuck with striper rigs armed with non-inline circle and standard bait holder hooks, as these will most likely be on closeout and are a catfish hunting bargain.

Not to be overlooked are jigs and slow rolling crankbaits during the early spring and again during late autumn. “I had blue catfish absolutely crush jigs I was working for largemouths on the Susquehanna Flats,” shared Smith, adding that it was an early spring tournament but the water was warming quickly and the blues were on the swarm.

“The sky’s the limit” high expectations for trophy fishing opportunities maybe not a good thing considering the eventual, and inevitable impact the blue will have on Delaware River ecosystems in the form of monster predation and the resulting scarcities that will impact long standing residents, namely largemouth (and eventually smallmouth) bass, walleye, striped bass, channel cats and migrating shad and herring. Panfish like rock bass, white and yellow perch, and forage like suckers, fallfish and chubs? Inhaled in the whiskered maw vacuum.

For now, it’s a kill upon catch directive from the Bureau of Freshwater Fisheries when it comes to the blue, same as the flathead catfish and the northern snakehead now populating more venues. Realistic? Not really, but the effort is proffered via identity in the article on page 36 in the 2023 Freshwater Digest with indicators identifying New Jersey’s non-invasive and invasive catfish.

“Vive le poisson-chat-bleu!”