Matching your angling outings to when target species are most active

With the official last day of summer on September 23, we can officially talk about this as being “the fall run” along the Atlantic Coast! Of course, October can be a tricky month; sure there are plenty of treats, but we’re still in the heart of the Atlantic Coast tropical storm season, and at any point in the next two months we can expect that bout of “second summer” referred to by the American Meteorological Society as a period of abnormally warm weather that occurs in mid- to late autumn and after the first frost.

But the days continue to grow shorter, and nights bring a continued cooling of air and water temps. This signifies to our favorite coastal gamefish, and the prey they seek, that it’s time for a move. In many instances, it might also trigger the “snow bird” preparations for their upcoming migration from the Northeast to resort areas along the Florida coast.

Ignoring human-based modifications, like heavy clothing or travel bottles of iced water, at what temperature are you most likely to be found being active? The optimum comfortability range for most people is between 60 and 85 degrees. This is clearer when considering the higher numbers of people engaged in outdoor sports and at parks across these temperatures. Most in-house thermostats are even set within this temperature range; that’s because human physiology has evolved to work optimally within a certain temperature range.

Other organisms, too, have preferred temperature ranges to which they can be found most active. Yes, even the main gamefish for which us anglers constantly target! Armed with that knowledge, an angler can more effectively match their target species and angling strategy to the water temperatures and time of season.

Before diving in, let’s appreciate that the following information are generalities. They can/are used to improve angling performance, but like anything else in life, there are extensions and exceptions to these guidelines. At least one of these “extensions” will be highlighted in the description of striped bass.

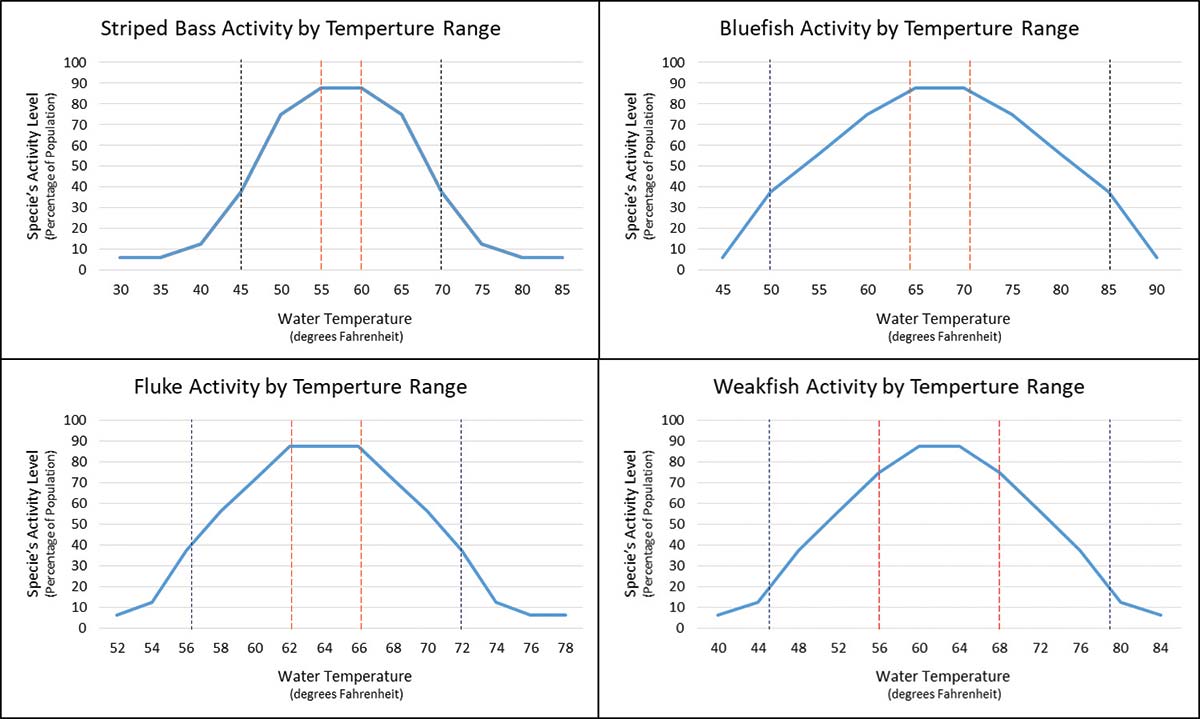

The species’ activity level on the example graphs below do not hit 100% or 0%. This is because no matter how optimal the conditions, not all fish in a population will be actively feeding; and no matter how far outside their temperature range, there is always some minute chance of catching a single individual.

False albacore (Euthynnus Alletteratus) and Atlantic bonito (Sarda Sarda) are related but distinct species that can linger in our region well into October. Names and nicknames for these fish are often misused and conflated; as you’ve seen previously in The Fisherman at some point down the road, bonito in the single “masculine” form might often be spoken as bonita as a singular “female” word, but they’re not the same. In many Southeast states the word bonita is often used to refer to a false albacore, creating some confusion between the more edible bonito.

Let’s overlook these species’ differences, though, and collectively focus on two of their similarities, behavior and temperature range. False albacore and Atlantic bonito can be caught in water temps from about 58 to 80 degrees, but aggressively chase down their prey between 67 and 73 degrees. To subdue them, any shiny type of lure like a Deadly Dick, Hopkins or epoxy style jig will work. This not only matches the hatch in prey they’re likely seeking, but it catches their eye. Also, such lures are durable against the bonito’s teeth and either species’ strike impact. Just be sure to keep the interest of these fish by reeling fast. After all, evolution refined them to live in the fast lane.

Striped bass start being more active around 45 degrees and remain so into the low 70s. The zone in which stripers are most active, and most likely to find them blitzing on live bait or plugs, would be from about 55 to 62 degrees. Toward the ends of this range, bass usually prefer stationary baits, like worms, clams, crabs, and chunks. Near the higher end of their temperature range crabs can work well. Worms and clams work particularly well on the colder end of the temp spectrum. This is not just because they are stationary and require little energy expenditure to consume, but likely too because the soft tissue is easily digested.

An obvious exception to these principles would be pre-spawn cow stripers, high on hormones, feeding well below their predicted temperature range on herring and shad.

Bluefish are normally and justifiably thought as the eating machines. Unlike the energy-optimizing ambush tactics employed by the others, bluefish more actively hunt their prey. This does not mean they act the same across their entire temperature range, which is about 50 to 84 degrees. Toward the extremes of that range they can be more picky, sluggish, and lower in the water column. Some of the first cold-water bluefish to be caught each season at the southern end of The Fisherman’s readership range (i.e. Jersey Shore and Delaware coast) are taken on stationary chunks or jigs worked slowly along the bottom of inlet water columns.

From about 64 to 72 degrees is the bluefish sweet zone, where they behave like piranha of the ocean. In these temps, they are liable to hit a tin can with a hook. When blues are more active, it is most important that an angler take caution, using pliers to avoid the gnashing teeth.

Summer flounder or fluke have a more narrow temperature range than the previous species, generally caught in temperatures ranging between 56 and 72 degrees, with their peak activity occurring in the 62- to 66-degree water temps. Live killies, squid strips, or variations of Gulp and Fishbites are often the best for enticing them. To do so effectively, an angler must cover the bottom with their offering due to the fact that fluke are primarily ambush predators. From bulkheads, piers, and other shore-based positions, one can cover ground with their offering by walking their rigs.

The main temperature — dependent adjustment that can be made in fluke fishing strategy would be the speed in which the presentation covers ground. This author would recommend a slower retrieve, drift, or walk nearer to their temperature extremes; this is due to their potential lethargy at such times. During their peak range, one can be more liberal with speed, insomuch the presentation remains on/near the bottom, where these flatties lay.

Weakfish have a wide temperature range, from lows near 45 degrees to highs up around 78 degrees. Like striped bass, they tend to be more sluggish and lethargic near the ends of this range. In such contexts an angler may want to use soft stationary baits like bloodworms, or at least know to work their soft plastics a bit slower in the water column. Understanding this should help an angler adjust the times and strategies by which they target weakies, but also to modify the rate by which they fight one.

Weakfish in their most active water temperatures (about 56 to 68 degrees) are sure to put up a tougher fight, and doing so could put undue pressure on their ‘weak’ jaws. Therefore, erring toward a looser drag in these conditions may enhance both the landing potential and safe release of a weakfish.

| SWEET SPOT |

| The author, a science professor at Stockton University in New Jersey, compiled this chart of temperature ranges for the big four inshore species (clockwise from top left) including striped bass, bluefish, weakfish and fluke, with the dotted vertical red lines in the middle representing the sweet spot for success.

|

It is essential to appreciate the correlation that preferred temperature ranges have with effective catch and release practices. Minimizing handling and the time a fish is out of the water are always important. These practices should be emphasized, however, when fish are taken from waters on either extreme of their preferred temperature range. This is because they are more vulnerable to harm in such states. In fact, leaning toward tighter drag in these conditions prevents excess exhaustion in the fish. To appreciate this better, imagine wrestling someone who’s attempting to subdue you after running a sprint in 65-degree weather versus 100 degrees. This former is tough, but doable, while the latter is a certain trip to the hospital after fainting.

The way in which to most accurately gauge water temperatures is by viewing the closest USGS buoy readings online. Some fishing locations may be distant from such, in which case having a handheld water thermometer always comes in handy. Recording the temp readings to when fishing is poor versus great can add a nuanced understanding to how the water temperatures affect the productivity of a specific spot. This knowledge will allow an angler to better anticipate feeding behaviors of the target species for the future.

Many variables can influence local water temperatures, such as wind direction, clear versus cloudy skies, and precipitation. Understanding how these factors do so can seriously enhance one’s angling ability.