Nine potential flatfish you’re apt to encounter on local waters this season.

There are nine species of flatfish that are found in our Northwest Atlantic waters, including winter, summer, windowpane, four spot, witch, and yellowtail flounder, along with the hogchoker, American plaice and Atlantic halibut. The challenge with so many different species of flatfish is how to identify one from the other. They all live and feed on the bottom in similar habitats; they are all flat and generally football-like in shape, so how do you tell them apart? The first technique in whittling down the pool of potential suspects is to know which fish is most plentiful in what regions of the Atlantic, from Delaware north to Canada.

Winter Flounder

Winter flounder (pseudopleuronectes americanus) are the most abundant species of flounder found north of Cape Cod and throughout the entire Gulf of Maine. This species is also known as sole, lemon sole, Georges Bank flounder and blackback flounder. They can be found in estuaries, out to the continental shelf in the Northwest Atlantic, and range from the Gulf of Saint Lawrence in Canada south to northern North Carolina.

This species is a right-eyed flounder, with very full, robust large puckering lips extending out just in front of their eyes, and have a straight lateral line. No other species of flounder found in the Northeast has large puckering lips directly in front of their eyes. If you see large puckering lips in front of the fish’s eyes, bingo, you have just identified a winter flounder.

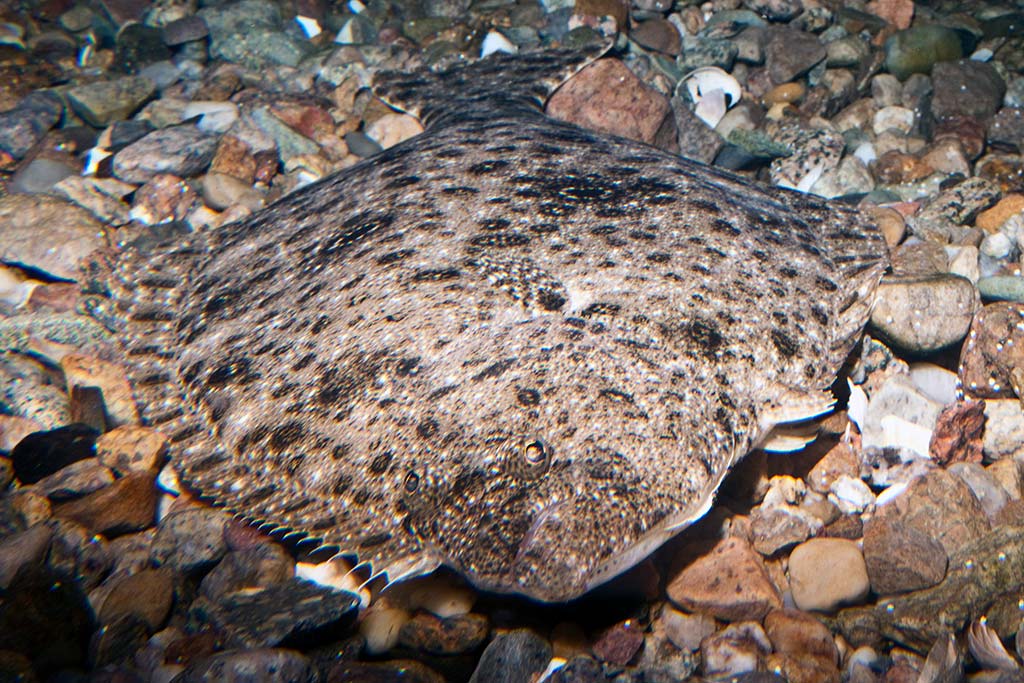

All flatfish use camouflage to hide from predators and blend in on the bottom. They will cover themselves with sand or mud to increase their chances of survival from predation. However, here is where things get interesting – newly hatched larval flounder of all species, have one eye on each side of the head and swim vertically in the water column just like every other fish in the sea. As they develop, the eye that migrates to the top of the animal will determine if the flounder is a right-eyed, or left-eyed, and further fine-tune what species you are currently looking to Identify. At this stage, they are so small you cannot see them with the naked eye. Five to six weeks after they hatch, larvae settle to the bottom to begin their metamorphosis into juveniles. After spending several weeks growing, and living on the bottom, their left eye will move to the right side of their body and that is when they start to look like the flounder we all know and love to eat.

Summer Flounder

Summer flounder (paralichthys dentatus) are found from Massachusetts south to Florida on the Atlantic Coast. They are the most abundant flat fish from Cape Lookout, NC north through Delaware, but have been observed and caught as far north as Maine. In Massachusetts, summer flounder are frequently caught on the north side of Cape Cod in Cape Cod Bay every summer and fall, but are more abundant on the south side of the Cape and all points south.

This species has a large angled mouth with sharp serrated teeth; both dorsal and anal fins are symmetrical and separated considerably from the anal fin. Known better regionally as fluke, the summer flounder are a left-eyed flounder, not right-eyed. These are your first critical clues that this fish is not a winter flounder, but something else.

Here is how you tell the summer flounder, also known as a fluke from other flatfish in your area. Summer flounder have three distinct ocellated brown spots on their back near the tail on the left side, or top of the fish, and white on the right side, or bottom. An ocelatted spot is one that has a dark brown dot in the middle, surrounded by a white halo, or ring. Their body is oval shaped, somewhat resembling that of a large, flat football.

All flounders will camouflage themselves under a thin layer of sand to avoid predators, and change their skin pigmentation to better blend in with the bottom they are laying on. Once buried under the sand all you will see are two small eyes staring and following you if you are swimming along the bottom. As a SCUBA diver or snorkeler, this makes a positive identification of this specie next to impossible without seeing the entire body and its’ distinct markings.

Windowpane Flounder

Windowpane flounder (scophthalmus aquosus) is another left-eyed flounder whose name helps identify it. These fish are quite literally windowpane thin. If you hit the top of this fish with any light source, you can easily see right through the body. If for example you held the fish up into the sun, you would be able to see the sun right through the fish’s body.

The second way to make a positive identification is to look closely at the leading edge of the dorsal fin rays. These fin rays will extend beyond the opening of the fishes mouth. Finally, windowpane flounder are almost completely round in shape, not football shaped, and elongated like the rest of his/her flatfish cousins. They are not very good eating and usually caught as by-catch. There is simply not enough meat on this guy to make it worthwhile to harvest.

Hogchoker

The hogchoker (trinectes maculatus) is the smallest flatfish in our region. They are also very easy to tell apart from other flounder. First, this species seldom grows larger than approximately 8 inches in length, so who would keep it if brought on the boat, or shore. They are also called a freshwater flounder due to the frequency in which they are found well up freshwater drainages along the coast.

To my eyes (see the photo of The Fisherman’s Matt Broderick with a hogchoker), this species looks like the tail fin has been chopped-off at the halfway point upon first observation of this little guy. Hogchokers have the oblong shaped body of other flatfish, but they have a rounded snout and do not have a pectoral fin what so-ever. If you catch a small flounder with a rounded snout and no pectoral fin, then you have a hogchoker.

This is also a right-eyed flounder, which is another way to tell it apart from other more commonly caught flounder species. Hogchokers have a straight lateral line, and I have seen some specimens with thin lines that go against the grain so to speak, and run perpendicular to the lateral line on the fish’s body.

Five Wildcards

While the four previously mentioned flounder species are a little more common for regional anglers, depending on your latitude, there are five other flatfish that you may, or may not ever see at the end of your line.

The four-spot flounder (paralichthys oblongus), also called the American four-spotted flounder, is a fish that in my over 40 years of scuba diving, have never observed in the wild. This is most likely because I conduct most of my diving activities north of Cape Cod. Location is key in terms of identification since literature states that the four-spot flounder is found from Georges Bank south to Florida, which makes the odds pretty unlikely of my ever seeing this flatfish while scuba diving anywhere in the Gulf of Maine.

This species is a left-eyed flounder with four, distinct, ocellated spots – two about half-way down their backs, and two just in front of their tail fin. This is a critical identification clue, as no other flatfish has these markings found in the same location. I have also seen dive buddies photos showing regular white to brown perpendicular patches of color running the length of the fishes body – no other flounder will exhibit this color pattern.

Witch flounder (glyptocephalus cynoglossus) is another easy fish to identify. This species is a right-eyed flounder, but does not have any recognizable scales over its body, but in fact has fine, smooth scales. They have a relatively small head and mouth and are narrower and less oval than most other flatfish. Another ID clue is the topside pectoral fin is sometimes black, or dusky in color with a narrow light, faint border. No other flounder in this part of the globe have this coloration on their pectoral fins.

Yellowtail flounder (limanda ferruginea) are a thin-bodied right-eyed flounder that is found throughout our reading area. They are wide-bodied flatfish, almost half as wide as they are long – with an oval shaped body. They have a small mouth and an arched lateral line. Their upper side, including the fins, is brownish or olive, tinged with red and marked with large, irregular rusty red spots. Like so many of our fish, this species got its’ name because their tail fin and the edges of the two long fins are yellow. The underside is white, except for the area between the body and the tail, which also has a yellowish hue. If you catch a flounder with yellowish fins, then bingo, you probably have caught yourself a yellowtail flounder!

Our final two flatfish are less likely to be caught by inshore coastal anglers, as these are both cold, deep water flounder species. The first is the Atlantic halibut (hippoglossus hippoglossus), the largest species of flatfish in the world which can grow to lengths of up to 15 feet. When looking at the anatomy of this fish, one thing jumps out as different from every other flounder species. Look at the tail fin – it is deeply forked and not rounded, or squared like every other flounder species. Their size is also an amazing tool for identification as well. If you catch a barn door halibut 5 feet in length you can be sure it is a halibut.

Finally, we have the American plaice (hippoglossoides platessoides). This is another larger flatfish found in the deeper waters of the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary. To me, this right-eyed flounder appears to have had all of its scales removed and has a smooth back. This species also has a large mouth that reaches below the rear edge of their eye and a classic rounded tail and straight lateral line running the full length of their body. They also have a unique coloration of a reddish-brown pigmentation on their backs.

So, what kind of flounder is that? I think you now have a much better idea of how to tell these tasty flatfish apart from one another.