He was a rude, tightfisted and surly old man; the last person I would have ever chosen to become my friend. Old Jack was a retired mill worker who owned the neatest two-family home in our blue-collar neighborhood, and unfortunately my favorite Aunt Vi and her husband Ted moved into their vacant apartment while their new home was being built. On my occasional visits to her residence I would encounter the old man who patrolled his property with the tenacity of a pit bull, particularly when the local school bell rang, and the children walked by his property on their way home. Not wanting to put my relatives in an uncomfortable position, I was always extremely polite although the friendliest response I ever got out of that curmudgeon was a grunt. After watching me come and go for months his tolerance grew to acceptance but never anything resembling friendship. Several months later, on the way home from a hunt, I raced to my aunt’s house late one Saturday afternoon to pick up some raisin squares she baked for us.

As I exited the house Jack was standing at the rear of my station wagon looking on the rear deck. Although he never owned an automobile he took great pride in his driveway with its silver chain link gates and prominent NO PARKING sign. Jack patrolled this zone enforcing his ordinance, backing you off if you ventured close to the private break in the curb. I’d broken the cardinal rule by parking directly in front of this prohibited zone, so I walked up to him eyes downcast expecting to be chastised. “You hunt?” He mumbled.

“What?” I asked. Those were the first words he ever spoke to me. He pointed to the brace of pheasant on the rear deck of my station wagon. “Yes,” I responded, “Would you like a bird?” He made an awkward attempt at a smile, took the bird and walked off without so much as a thank you; but at least I didn’t get bawled out.

The following day my aunt called and told me Jack wanted to see me before supper. Probably to complain about the shot in the bird, I thought. With nervous trepidation I knocked on his door. His gracious wife Georgie greeted me with a warm smile and pointed to the kitchen where Jack sat at the gleaming chrome dining room table smoking his pipe and tapping the stub of his right index finger. He pointed to a chair then walked out of the room, returning with a clean-yet-ancient 4-quart covered saucepan. He smiled as he opened the cover under my nose. “Pheasant stew.” he said. “Eat it for supper and don’t forget to return my pan.”

My wife had already prepared supper, but we put it away for the next day and feasted on Jack’s scrumptious concoction. I dutifully returned the pan that night after my bride wore out three Brillo pads trying to get the aged burn marks off that ancient vessel. The ice was finally broken, and fishing and hunting became our connection.

Some might think that the memories of the early Christmas seasons for a poor boy whose father had passed when he was only 12 might be of unfulfilled desires and anxiety, and to some extent it was. What saved me were the people around me. My sainted mother and the nuns who preached the gospel of accepting that “it was better to give than to receive,” a prescription that was usually hard to swallow. Then I began to understand how my poor mother, with so little of her own could share a bowl of soup or an old sweater she repaired with someone who was destitute. Her mantra of, “just look around and you will always find someone who is needier than you.” I took her at her word and did just that.

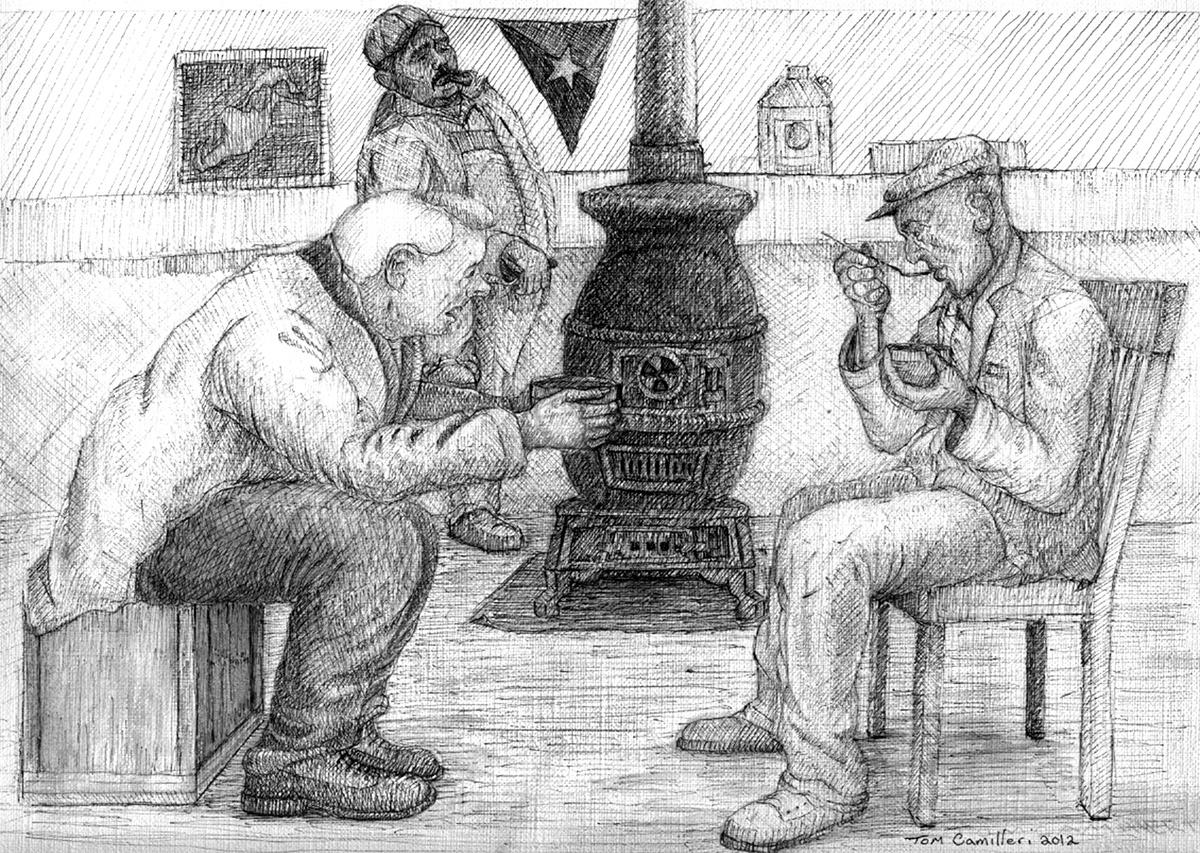

Many of my mentors at the boat house were WW II veterans who suffered some form of disability as a result of their service, and none of them were well-off. Many were single or widowers who lived alone, most on small VA pensions that barely put enough food on their tables or tobacco in their pipes. Many wore threadbare military clothing and hand-me-down coats and shoes. At least two I knew well slept in an old armchair with a few blankets to keep warm and save money by not using their kerosene heaters unless it was frigid. I had visited a number of those apartments, delivering food and tobacco from their comrades at the club. One of those flats was so cold there was frost on the inside of the glass that had never seen a storm window, only a few old towels stuffed in the sills to keep the drafts out.

At that stage of my life I was struggling to provide for my family; working two jobs to pay my bills and attempting to put a few dollars aside for those bumps in the road that were sure as certain, as the hard times we all experience. Jack became a different type of mentor because early on in our relationship he often put me to the test. Because of his failing health he was unable to fish and hunt, and was using a cane, or clinging to furniture, to get about his house and yard. He begged me to take his dogs to hunt and exercise them, but that was one request I never granted. Those beagles only knew me through their kennel’s fence, and the thought of returning home without one or both of his beloved hounds was a risk I would not take. I did take his ancient 12-gauge double barrel hammer shotgun, an antique firearm that dished out punishment at both ends, to grant his wish for a brace of rabbits for his traditional Christmas rabbit stew. Jack was one of the best bridge and pier fishermen in the area, and he missed those baked stuffed tautog. One late November he really put the pressure on me to catch a tautog for his Thanksgiving weekend dinner because he hated leftover turkey. That was a bitter cold November, but the stars aligned and along with Jack’s and my bride’s prayers I caught one husky tautog causing that old man to be as happy as I’ve ever seen him.

While I was running errands for the patriotic crew of watermen at the Weetamoe Yacht Club, I was aware that so many of them were poor, a few living in abject poverty. They survived by helping one another and lived from one small pension check to the next. I understood all about living in poverty, but in my case I had my mother and a younger sister and brother, and we actually never felt impoverished because of the miracles my mother was able to create out of thin air. She was our safety net.

Back then very little cash changed hands between the members; because these were the men who refined the bartering system. They didn’t call it bartering; they usually referred to it as a “swap” of a favor or service for something in kind. There wasn’t anything I could buy or make for Jack, and I really wanted to give him a special Christmas present as he was nearing the end of his days. He once told me that for all the 60 years he had hunted he had never seen a deer or any sign of one, and I recall him saying that before he died he would love to cook and taste a piece of prime venison.

There were few if any deer in our area at the time so hunting one was out of the question. There was a member of the club the men referred to as a high roller who had a handsome boat, a new Mercury 20-horsepower outboard and a new shiny Oldsmobile 88 roadster. Every fall he went off with a group of men from his college days to hunt in the big woods of Pennsylvania, and I had seen photos of the deer he had bagged on those trips.

One afternoon when he was cleaning out his locker I summoned the courage to ask him for a favor. I told him if he could spare a piece of venison for my old friend I would sand and paint the bottom of his boat that spring free of charge. “Well that sounds like an offer I cannot refuse, and I just happen to have a few venison steaks in the freezer. How soon do you want one?” he asked. Two weeks later I visited his house and was invited in. He took me to a side room he called his den, but it was more like a high-end tackle shop with rods, reels, shotguns, rifles and all the trappings of an outdoorsman. I was mesmerized. Prior to this visit we had never shared much more than a casual relationship with me running the occasional errand or bailing out his boat after a heavy rain. I spent nearly two enlightening and enjoyable hours in that room and came away with two big venison steaks, a new spool of 36-pound Cuttyhunk linen line and full box of Virginia tautog hooks.

When I told him I could not accept these gifts he provided an explanation that has influenced me to this day. “You came here offering a considerable service to help make an old friend’s wish come true. Because you are doing something for another person with no thought of personal gain, I’m impressed. Although I am living well it wasn’t always like this. We have a lot in common because I also lost my father at a very young age, and friends and family got us though those very difficult times.” He took my hand, wished me a Merry Christmas and insisted that I would be paid for my work on his boat that spring and he would not take no for an answer. I walked home, thoughtful of what had just taken place realizing there was a kind heart in the man I once considered wealthy and aloof. Jack finally had his venison in the form of a perfectly-cured steak, and my mother worked wonders with the other piece he insisted I bring home to my family. I readily admit it was difficult for me to accept my mother’s resolve that it was better to give than to receive, but after observing and benefiting from her generosity I became an advocate of her teachings.

December and the weeks leading up to Christmas have always been a very special time for me. Even when money was tight, and gifts were scarce I was blessed with the company of elders from numerous backgrounds who helped shape my life. If you are so blessed with the friendship of such an individual be sure to express your appreciation. I miss those old timers, and their love for God, country and their fellow man and I hope to meet them again at the top of the mountain after the sun goes down.