In case you didn’t see our news update posted earlier this year at TheFisherman.com (ICCAT Takes A Bite Out Of Mako Fishing With New “No Harvest” Rule), the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas or ICCAT has shut down the North Atlantic shortfin mako fishery for the 2022 and 2023 seasons.

On December 13, 2017, based on the results of ICCAT’s stock assessment for North Atlantic shortfin mako sharks, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) determined the stock to be overfished with overfishing occurring. Through an interim final rule using emergency provisions in the Magnuson-Stevens Act (MSA), NMFS temporarily and immediately implemented commercial and recreational measures consistent with ICCAT Recommendation 17-08. The measures in this interim rulemaking focused on maximizing live releases of shortfin mako sharks, allowing retention only in certain circumstances, increasing minimum size limits, and improving data collection in ICCAT fisheries (83 FR 8946; March 2, 2018).

NMFS initially preferred (Alternative B3) increasing the recreational minimum size limit to land shortfin mako sharks, male or female, to at least 83 inches fork length (FL). This alternative would have implemented the same requirements that were in effect under the emergency interim final rule, which differed from the provisions in ICCAT Recommendation 17-08. However, based on public comment and updated analysis, NMFS adopted the preferred alternative B2, which increased the minimum size limit for male shortfin mako sharks to at least 71 inches FL and female shortfin mako sharks to at least 83 inches FL. According to the Standing Committee on Research and Statistics (SCRS) at ICCAT, it’s assumed that 50% of these fish might have spawned.

This minimum size is consistent with the provisions of ICCAT Recommendation 17-08 and was expected to have conservation benefits sufficient to achieve the objectives of the action by reducing shortfin mako mortality. This might have worked, but only if every member nation achieved the necessary reductions; but not everyone played by the rules.

NMFS also projected that these measures could result in a significant reduction in directed fishing trips for shortfin mako sharks, thus leading to moderate adverse socioeconomic impacts on supporting businesses and industries such as bait and tackle suppliers, marinas, and the hospitality industry in coastal towns.

However, based on their statistical analysis, NMFS projected that these recreational size restrictions on makos would have only a minor beneficial impact conserving the species, while posing a moderate adverse socio-economic impact to local coastal businesses that rely on shark trips and tournaments for annual income. Once again the United States was leading the way with her chin and was slapped down by the other non-complying ICCAT members.

Mako Stock Assessment Study

The basis for ICCAT’s current mako recommendations, which currently consists of 52 contracting members, is research conducted by their SCRS which is responsible for developing and recommending all policy and procedures for the collection, compilation, analysis and dissemination of fishery statistics. It is the SCRS’ task to ensure that the commission has available at all times the most complete and current statistics concerning fishing activities in the Convention area as well as biological information on the stocks that are fished. The SCRS also coordinates various national research activities, develops plans for special international cooperative research programs, carries out stock assessments, and advises the Commission on the need for specific conservation and management measures.

As such, a blue shark, porbeagle and shortfin mako study was conducted in 2019 based on 2015 data. An excerpt of this ICCAT study surmised that, “Blue shark, shortfin mako and porbeagle are large pelagic sharks that show a wide geographic distribution; the first two from tropical to temperate waters worldwide, while the porbeagle has a distribution associated with cold-temperate waters. Shortfin mako and porbeagle have reproductive systems that limit their fecundity, but increases the probability of survival of their young.”

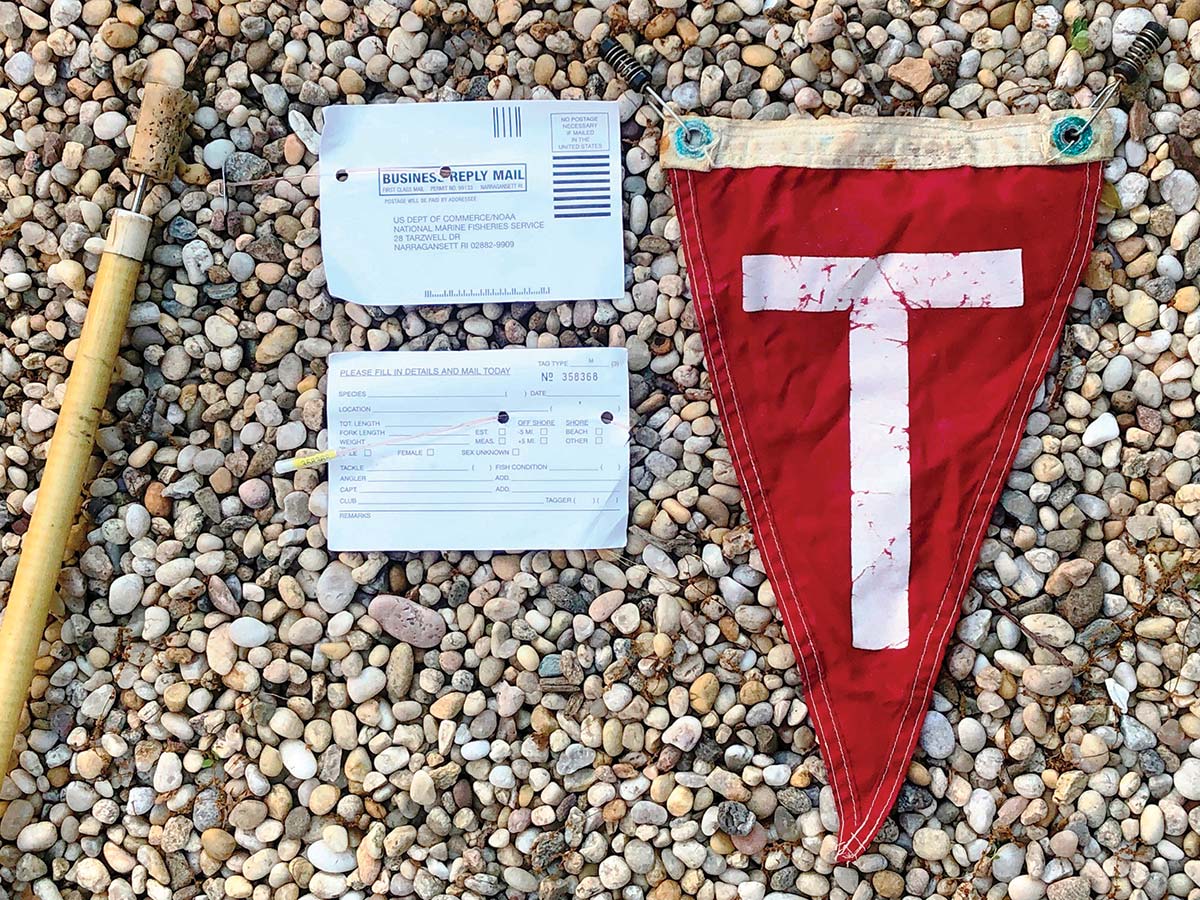

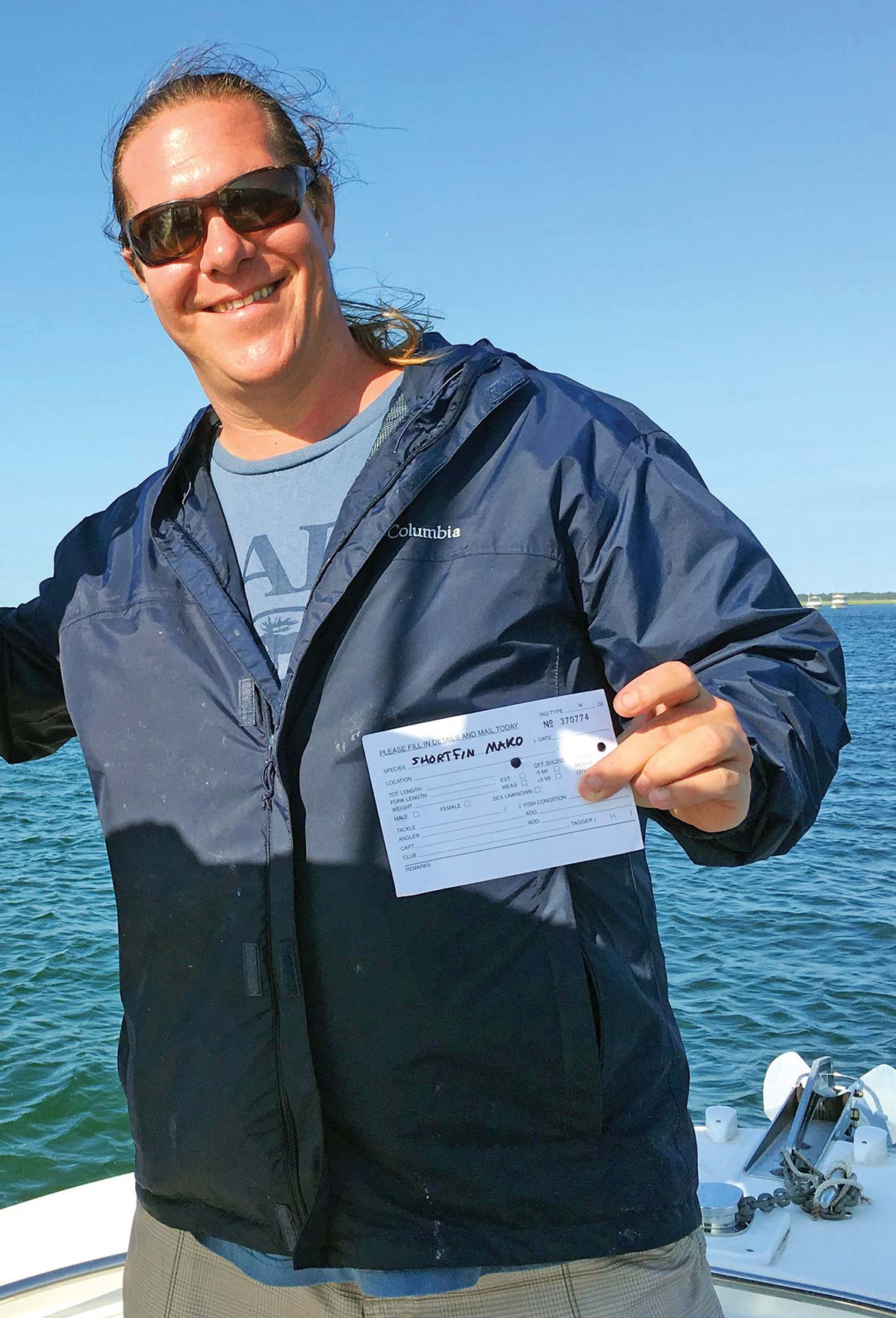

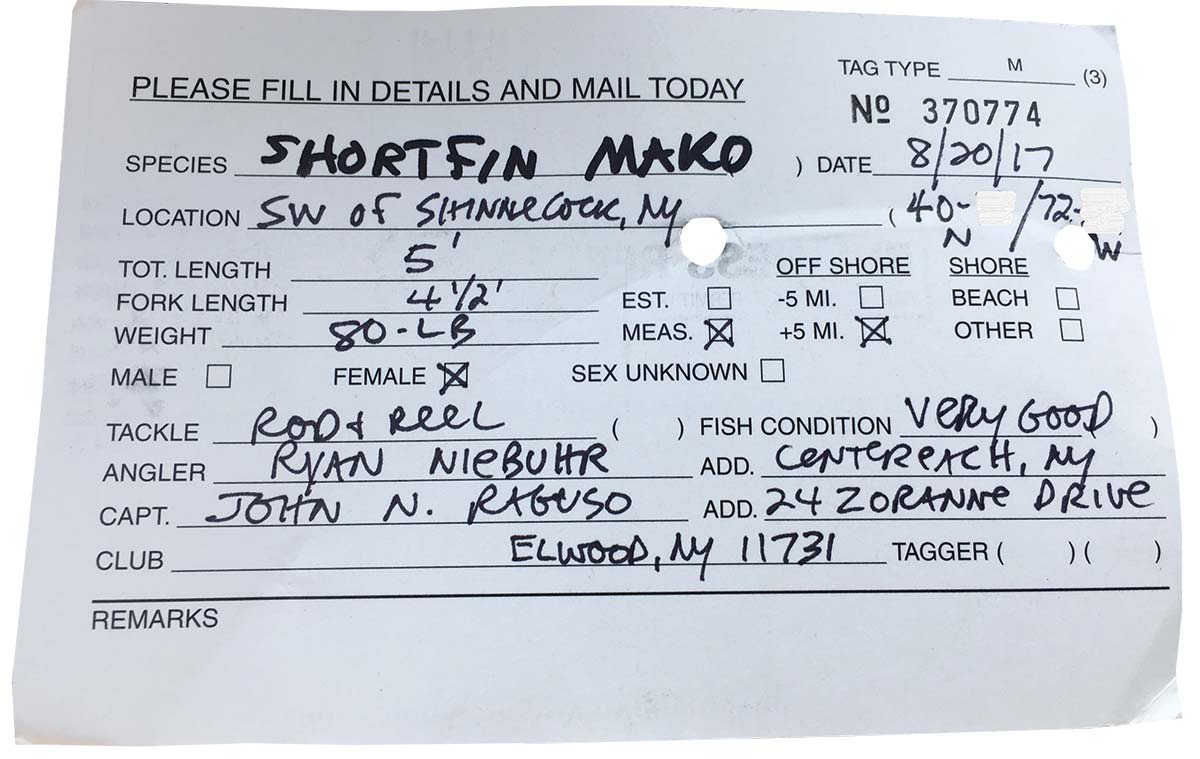

This particular ICCAT study found that the shortfin mako has an average litter size of around 12 and the porbeagle a litter size of usually just four individuals, and while high uncertainty regarding their biology remains, available life history traits (slow growth, late maturity and small litter size) indicate that they are vulnerable to overfishing. “Tagging studies have suggested that they exhibit largescale migratory behavior and periodic vertical movement, but the lack of information on some components of the populations precludes a complete understanding of their distribution/migration pattern by ontogenetic stage and in some cases identifying their pupping/mating grounds,” the study noted, adding “Numerous aspects of the biology of these species are still poorly understood or completely unknown, particularly for some regions, which contributes to increased uncertainty in quantitative and qualitative assessments.”

The 2019 report that was the basis for ICCAT’s shutdown of the mako fishery for 2022 and 2023 continued, “There are no targeted fisheries of shortfin mako in the North Atlantic (Campana, 2016) but the species is taken as bycatch, generally in pelagic longline fisheries targeting swordfish, tuna and billfishes (ICES, 2017). It has also been recorded as bycatch in driftnet fisheries in the Mediterranean (CIEM, 2018) and recreational fisheries on both sides of the North Atlantic have also reported relatively large amounts of the species taken by this activity (CIEM, 2017).”

“Reported catches of shortfin mako in the North Atlantic exceeded 3,300 tons in 2016 (mainly by longline vessels) (ICCAT SCRS. 2017), which amounts to 130,000 individuals (Sims et al., 2018), and reported catches in the South Atlantic exceeded 2,600 tons on the same year (ICCAT, 2017b); however, catches are considered to be underestimated and landing data do not reflect the number of sharks finned and discarded at sea (Cailliet et al., 2009; ICES, 2017). The main countries that reported catches in the North Atlantic in 2016 were Spain (47% of the annual catch), Morocco (31%), the United States (5% recreational and 4% commercial) and Portugal (8%), respectively (ICCAT SCRS, 2017). In the Mediterranean Sea, total reported landings have ranged between 0 and 2 tons since 2007 (ICES, 2017).”

Let me call out one point made in this report, specifically the claim that ‘recreational fisheries on both sides of the North Atlantic have also reported relatively large amounts of the species taken by this activity’ seems like a bunch of fake news. There were no reported statistics for this on the eastern side of the Atlantic and U.S. recreational anglers were responsible for only 5% of the total annual catch in the study. Meanwhile countries like Spain, Portugal and Morocco combined to take 86% of the annual mako harvest with their longline fleets. And less than 10% of their boats have observers onboard, so who really knows what they are catching?

Another nuance of this report is that Spain is boating over 36,000 tons of blue sharks every year. And those are the ones that they are reporting…and what are they doing with those? Anyone who has ever taken a mouthful of blue shark meat will know exactly what I’m talking about. Bottom line, the mandatory mako conservation efforts imposed on recreational anglers by the NMFS with size limits, use of circle hooks and retention limits from 2018 to 2021 were nothing more than a baseless “feel good” effort that wiped out our coastal tournaments, losing tens of millions of dollars spent locally every year on fuel, bait, ice, tackle, food and dockage.

While this creates great public relations optics for the various non-governmental organizations (NGOs) of the world, showing that their lobbying efforts were “making a difference”, these restrictions had zero impact on the bottom line as statistically detailed above. We were just conserving more fish from 2018 through 2021 for the Euro longliners to decimate on their side of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

International Players & NGO’s

In addition to the 52 contracting members in ICCAT, there’s another class of ICCAT meeting attendees called “observers” who are allowed to both to monitor the proceedings and comment at the conclusion of the meetings to promote their initiatives and agendas. NGOs are loosely defined as nonprofit organizations that operate independently of any government, whose purpose is to address social or political issues which are often inconsistent with the interests of sport fishing anglers.

To demonstrate this point, most of these NGOs like Pew, the Ocean Foundation, Pro Wildlife, Sea Shepherd Legal, and others are all essentially “businesses” with a mission focus. A few of these are non-profit, and the jobs created internally at each organization can pay very attractive salaries (known as operating expenses) to those that work there, covered by the corporate and private tax-deductible contributions to their group. These positions typically include travel benefits and meal allowances when attending ICCAT meetings overseas.

Some of our U.S. ICCAT advisory reps I talked with for additional research on the topic commented on how many of these NGO folks were travelling first class and eating out at the fanciest restaurants with their fellow NGO members at these ICCAT events, while the rank and file ICCAT reps who were more concerned with solving fishery issues, were doing bargain burgers at the local bar.

To see where some of these folks are at regarding their view of the fate of the shortfin mako shark and what they think should be done, I’ll present a brief summary from each of their “official statements” from the September 2021 meeting that cancelled our mako season for 2022 and 2023. To view each statement in its entirety, simply log on to the ICCAT website at www.iccat.int.

Pro Wildlife

“While we welcome that in the new proposal an alternative version proposes a temporary retention ban for North Atlantic mako for 2022 and 2023, this still does not meet the precautionary approach and the recommended high probability of 70% for rebuilding the stock by 2070. Pro Wildlife therefore strongly urges ICCAT Parties to support an immediate and long-term retention ban, in line with the advice from the SCRS. They therefore recommend the implementation of a temporary retention ban at least until 2035, or even better until 2045 (the earliest point in time a recovery of this population is at all possible).”

Pew Charitable Trusts

“While SCRS scientists have warned of the highly concerning population status of the shortfin mako shark since 2017, Pew continues to stress the scientific advice that a ban on retention of North Atlantic shortfin mako is an important first step to begin recovery. We are encouraged by the progress made at the October intersessional meeting of Panel 4, where there was acknowledgement from even the most significant mako fishing parties that retention will not be possible in the next several years given the status of the population and the number of incidental interactions between makos and longline fishing gear. There should be no less than a 60% probability of recovering the population by 2070. This will be the longest ICCAT recovery plan on record. Therefore, it is important that the timeline is not delayed when new stock assessments are conducted or science is completed. And it must be clarified that the recovery deadline will be no later than 2070 in any future updates to the plan.”

The Ocean Foundation

“The Ocean Foundation appreciates this opportunity to encourage ICCAT action on the shark fishery management issues. This week marks the fifth consecutive annual meeting that has parties grappling with ICCAT scientists’ advice for rebuilding overfished North Atlantic shortfin makos. An inadequate management response to the SCRS 2017 advice has exacerbated depletion and risks a collapse that is irreparable in our lifetimes. We are pleased that ICCAT Parties have recently made time for makos and that support continues to grow for the cornerstone of the SRCS advice: a complete prohibition on retention. Such a ban is essential to achieving the substantial mortality reduction needed to reverse decline. We oppose any North Atlantic shortfin mako landing allowances because they run counter to SCRS advice for a non-retention policy without exception, create incentive for irresponsible fishing practices that ensure mortality (and) further delay a multi-decade recovery.”

Sea Shepherd Legal

“The imperiled status of the North Atlantic population of shortfin mako sharks (NA-SMA), as well as ICCAT’s role in conserving and managing this population, is a matter of great public interest and the subject of hundreds, if not thousands of social media posts and articles. Any decision that is not transparent, science-based and proportionate to the urgency and severity of the situation would risk losing the public trust. In making this decision, as outlined in the recent legal opinion by Rosello et al., ICCAT’s CPCs that are parties to the 1995 UNFSA, should be guided by their obligation to ‘apply the precautionary approach widely to conservation, management and exploitation of highly migratory fish stocks in order to protect the living marine resources and preserve the marine environment.’ To fulfill this obligation, a party must, among other things, ‘be more cautious when information is uncertain, unreliable or inadequate’ and obtain and share ‘the best scientific information available’ for improved decision-making. Applying this approach to the NA-SMA, Rosello et al. find that a precautionary approach in line with the UNFSA would require a temporary retention ban until at least 2035, preferably until 2045, an assessment we fully endorse.”

Global Tuna Alliance

“While we appreciate the progress made over the last months, we want to highlight that none of the current proposals will provide the desired outcome. The proposed retention ban of two-years is a good start, but too short to stop the negative trend. All calculations for potential retention are premature in the face of the lack of robust mortality data from past years, with no discards reported by most CPCs. Therefore, we urge all parties to reconsider the current proposal and agree on an extended period for a retention ban, ideally until 2035, but at least until new projections from a new stock assessment by SCRS are available. Throughout these years, improved data sets, including dead and live discards, could be collected, being essential for improved total mortality estimates as highlighted by the SCRS. This period could then be used to discuss the future approach and additional measures to reduce mortality, by effective avoidance strategies, and post-release mortality.”

Shark Guardian

“Shark Guardian appreciates that CPC’s (ICCAT Contracting Parties and Cooperating non-Contracting Parties, Entities or Fishing Entities) have agreed to collaborate on measures to begin rebuilding overfished Atlantic shortfin mako populations. However, this intent must be matched with concrete measures resulting in tangible positive results for sharks. Avoiding past failures is imperative if overfished shortfin mako shark populations are to recover. Improvements are urgently needed to save this shark population which will already take around 50 years to rebuild with a probability of 70%. Shark Guardian urges all parties to at minimum agree to a retention ban, at least until the date of the next stock assessment in 2026. At that date more reliable information on live and dead discards over a range spanning several years should have become available, including reported discards, which would allow for a better estimate of total mortality to be used for any future retention allocations.”

Shark Project International

“Knowing that Northern Atlantic shortfin mako will continue to decrease until 2035 we had hoped to see a retention ban at least until a time, when new scientific advice from SCRS based on a new stock assessment is available, or preferably until we have proof of this stock recovering. Therefore, Recommendation PA4-809D proposing a default retention ban for 2022 and 2023 only is a disappointing outcome after 5 years of negotiations and inadequate for a stock which is about to collapse and may not recover in our lifetime, if ever. We had certainly hoped for more but acknowledge the compromise, with de facto one year of no retention and an option to possibly allow some retention in 2023. Nevertheless, this falls significantly short of SCRS advice and a precautionary approach accounting ‘for many of the uncertainties and increase the chances for successful implementation and rebuilding of the NA-SMA stock in accordance with the best available scientific information’ outlined in a recent legal opinion. Notwithstanding this we believe ICCAT must account for the existing uncertainties and adopt 70% probability instead of the proposed range for stock rebuilding by 2070.”

While most of the aforementioned NGOs want to totally shut down the mako fishery for the next 10 to 50 years, it was curious to see the summary response from another group called Europeche, which represents the European long liners. In it they claim that the mako is “not in danger of extinction” and are requesting a minimum of 500 tons of annual catch for each CPC involved in the fishery for “research purposes.” Coming from the folks that bushwhack over 72,000,000 pounds of blue sharks every season, it’s fairly obvious what is driving their thinking.

There’s one thing that I know for sure as to what group has not caused this precipitous mako decline at the global level, and that’s U.S. recreational sport fishermen; but we are certainly going to pay for the sins of others which is clearly evident with our zero catch retention for 2022, 2023 and beyond.

U.S. ICCAT Reps Speak Out

I spoke to a trio of our representatives to the U.S. ICCAT Advisory Committee to get a better foundation to write this article. The information and guidance that they shared with me was critical to get a better understanding as to what was really happening with the ICCAT members and the current state of the North Atlantic shortfin mako shark. They are just as frustrated and disappointed as I am with how things got to this state. In fact, it seems pretty apparent that some European and North African long liners have been running amok and savaging both the North and South Atlantic pelagic fisheries. And it’s not just the sharks, but these fleets have been doing a number on juvenile yellowfins and bigeyes too off the west coast of Africa. The main problem is that ICCAT observers are on less than 10% of these member longline vessels.

So while Western Atlantic longline fleets in the United States and Canadian play more by the rules with circle hooks, onboard observers, and mono leaders to allow bycatch sharks a chance to break free, many foreign fleets are still using j-hooks and wire leaders to make sure that nothing gets away. Nobody is following our example, especially the folks that are taking the majority of the shortfin mako (and blue shark) catch.

Special thanks goes out to our recreational ICCAT Advisory Committee representatives Rick Weber from South Jersey Marina, Nick Cicero from the Folsom Group (Bimini Bay and Tsunami fishing tackle) and Massachusetts charter Captain Mike Pierdinock of the Recreational Fishing Alliance for bringing me up to speed on a variety of very complex international fisheries issues. All three of these reps reminded me that NMFS fought hard for recreational anglers to have a mako fishery from 2018 to 2021, but that most of the other ICCAT members wanted a complete shutdown, albeit it with a special bycatch for those pesky Euro long liners.

I had hoped that my initial conclusions from an article that I wrote a few years back about the state of the mako fishery were wrong and that things were getting better. That hope has been totally dashed and things are actually worse than I initially thought. To get a better understanding if their planned 2022 and 2023 mako shutdown measures will have any positive effect on the fishery, ICCAT’s SCRS is scheduling another shortfin mako stock assessment by 2024, with additional assessments planned for 2029 and 2034. If European long liners would give it a rest and perhaps focus on “decimating” other target species, maybe the mako shark will make a comeback in our lifetimes. Of course, there are no ostensible restrictions on the southern mako population and it’s not beyond these folks to claim that all of the makos that they have onboard came from down south; without fisheries observers onboard, it’s hard to imagine that not happening.

Bottom line, ICCAT needs to do a better job of having observers on all of these boats to ensure 100% compliance to the rules.

In the interim, I’ve been assured that our ICCAT Advisory Committee and reps will continue to fight the good fight, represent our interests both commercially and recreationally…and who knows, maybe a few mako miracles might happen.