The second largest New Jersey reef site offers plenty of solid structure.

Natural and artificial structure offering extensive fishing opportunities are just a short distance outside Manasquan Inlet. Getting safely through the inlet is the first challenge.

A most important lesson I learned about coastal inlets while growing up on a barrier island was – they don’t respect us, but we better respect them! Inlet conditions are continually changing over the course of the tidal cycle and with swell height and direction. Even where inlets are protected by rock jetties, that doesn’t mean smooth sailing. Cross currents at the opening can sweep a boat onto the rocks.

On an otherwise calm day, a sleeper ocean swell from a mid-ocean storm can sneak in, curl up as water depth decreases close to shore, break on shoaling in the channel, create confused surface conditions, and cause havoc for the unwary or unprepared. During strong ebb currents, standing waves can develop and interact badly with incoming ocean swells.

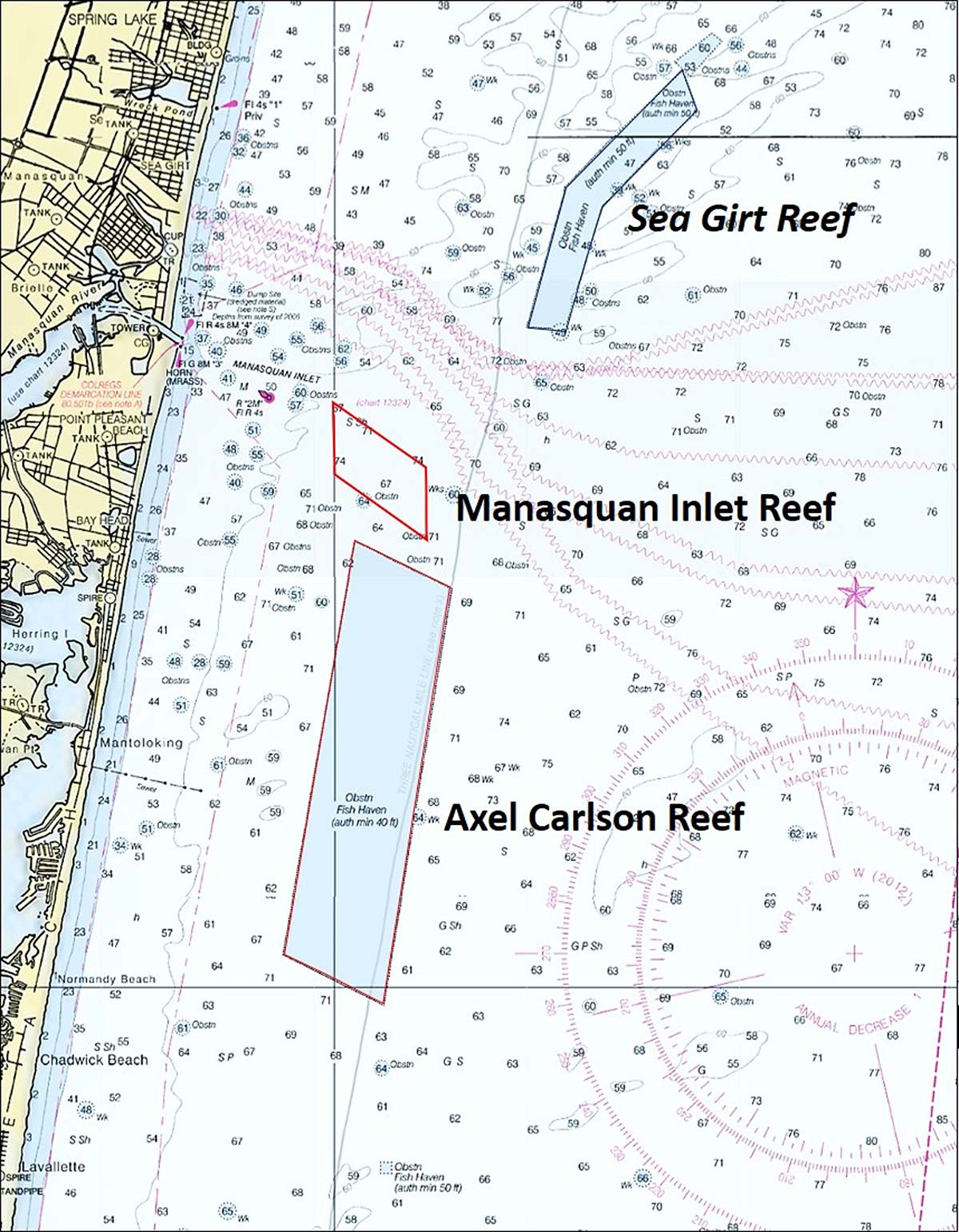

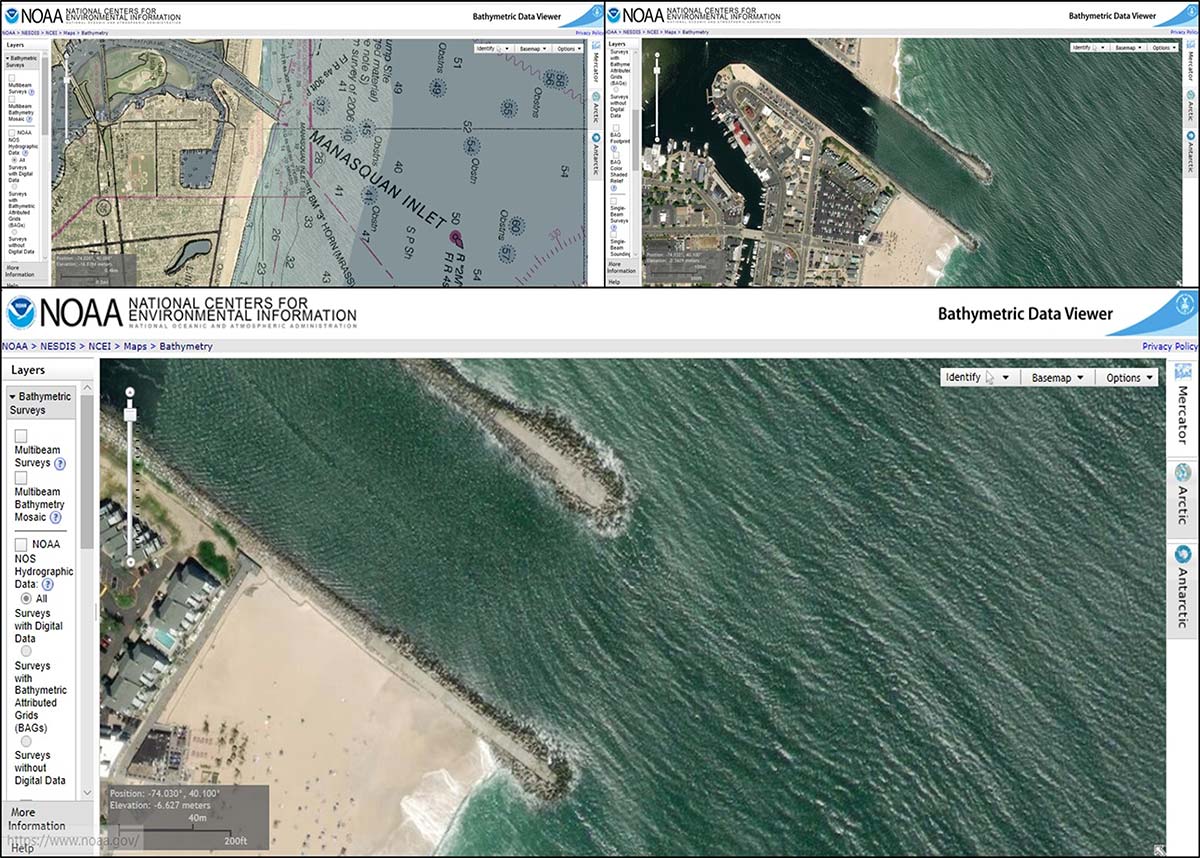

Manasquan Inlet is no exception. The net movement of sand along the North Coast is to the north, demonstrated by sand buildup on the southside jetty almost to its outer end. Sand migrating across the entrance can lead to shoaling. Inlet orientation also makes vessels vulnerable to broadsides from northeasterly swells that carry a short distance inside the entrance, as shown in CHART 1. These screenshots taken with the World Imagery (Esri) basemap displayed are from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Bathymetric Data Viewer (BDV).

Multibeam Sonar Snapshot

Assuming favorable operating conditions, about 2 miles outside the jetties is the new Manasquan Inlet Reef. Three miles south of the inlet is the well-developed Axel Carlson Reef. Each reef site is fully covered by the BDV “BAG” Color Shaded Relief image. The “BAG” image is a side-scan-like multibeam sonar image without the typical side-scan shadow. Generally, “BAG” images below about 40 to 50 feet are grainy because of pixel size. For Manasquan Inlet reef, the “BAG” image is pre-development. For the Axel Carlson Reef, some reef deployments have occurred after collection of field data that were used for the BDV display. “BAG” image clarity for these two sites is generally sufficient to identify reef characteristics for most objects.

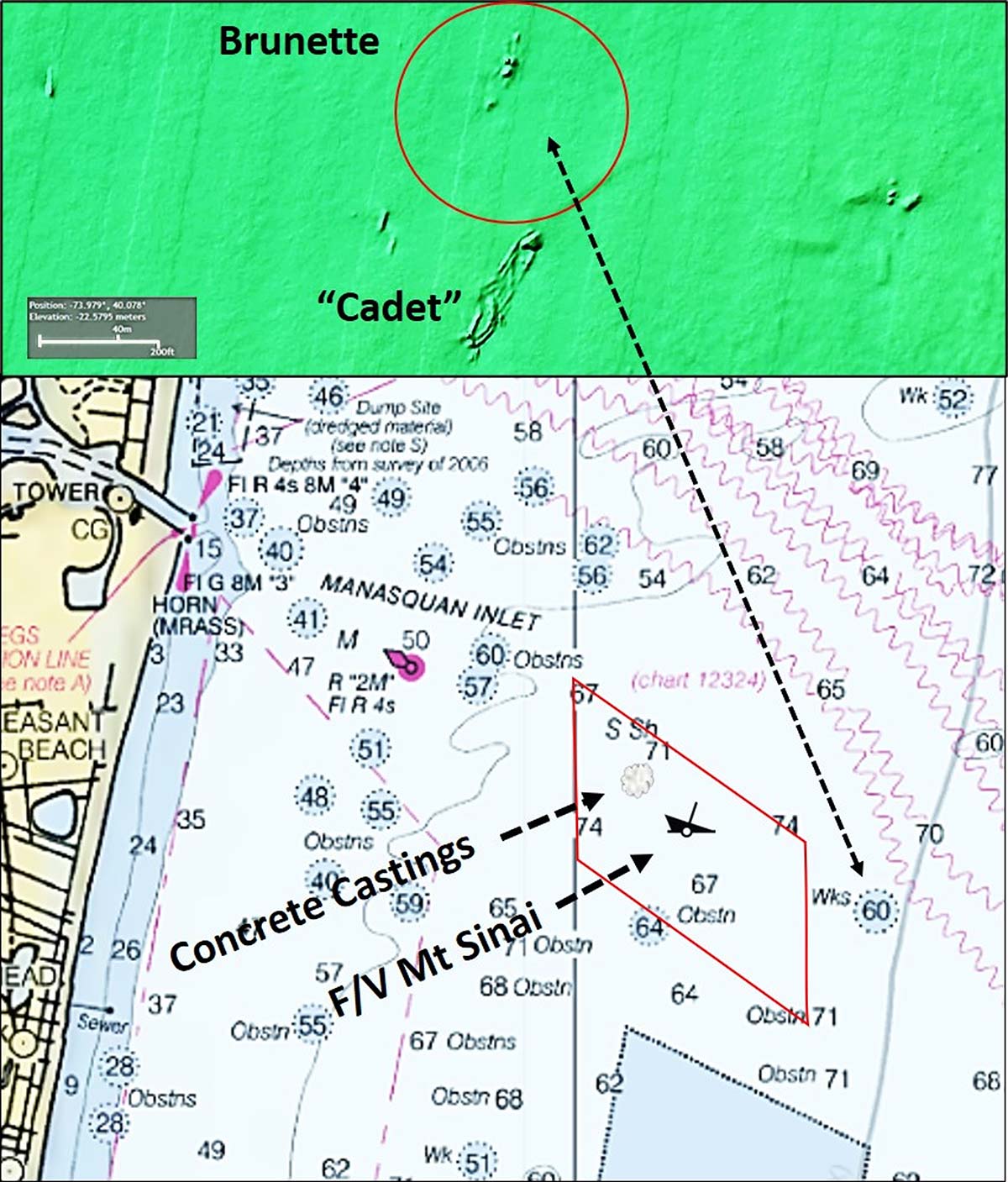

Development of Manasquan Inlet Reef began in 2017 with material of opportunity deployments. A ten-year buildout is planned by reef program managers. CHART 2 shows the approximate location of initial reef deployments as well as the location of several wrecks just east of the new reef’s boundary. The first artificial reef deployment consisted of concrete castings. Pictures on the reef program webpage show precast round manholes, square boxes, and pipes. The 87-foot fishing vessel Mt. Sinai was also sunk as a reef. Deployment pictures show fishing gear removed, although some railings remain (see list of past and prospective deployments at www.nj.gov/dep/fgw/artreef.htm).

Additional planned deployments include materials from demolition of the old Goethals Bridge, although a prospective deployment schedule is not posted.

Nearby wrecks are the Brunette (also known as the “doorknob wreck”) which sank in 1827 and Cadet which sank in 1870. The latter’s actual name is the John H. Winstead, but is commonly referred to as the Cadet. The latter’s wreckage is outside of the wreck circle. The history for these wrecks, detailed layout drawings, side-scan sonar image, and underwater pictures are at the njscuba.net website.

A Million Tons

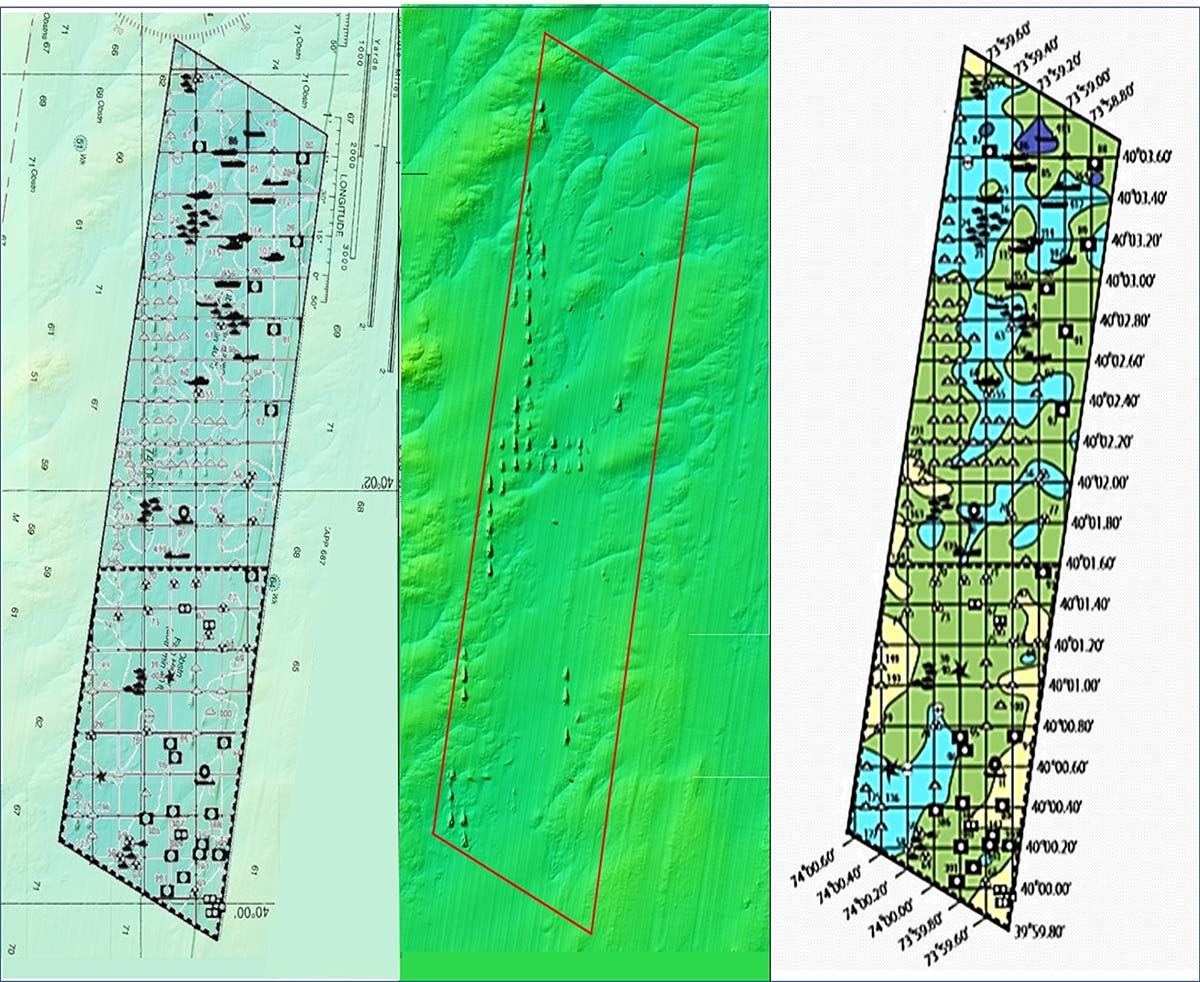

The first reef deployment to Axel Carlson Reef was in 1996. Since then, the site has received over a million tons of rock from New York Harbor dredging projects. Rock reefs are easily recognizable as teardrop shaped deposits. Some rock drops from hopper barges are on top of other drops, resulting in very high vertical relief. Think mini-mountain.

The reef program layout grid and table show more reefs than are visible in the “BAG” image; some deployments were made after data collection for the image. CHART 3 depicts the reef layout. It includes a basic version of the reef program grid overlaid on a see-though chart on top of the “BAG” image. Also shown are the “BAG” image with an outline of reef site in red, and the reef program color-shaded reef grid drawing.

Grid icons identify type of material and approximate location. Because of icon size and shape, the icons don’t align precisely with the reef objects they represent when the drawing is overlaid on the “BAG” image. The coordinates shown in the table keyed to the icons are more precise than those that can be extracted from the grid; use the former as way points. Coordinate accuracy is not specified, however. Some localized searching with a fishfinder and sonars should be anticipated for positioning.

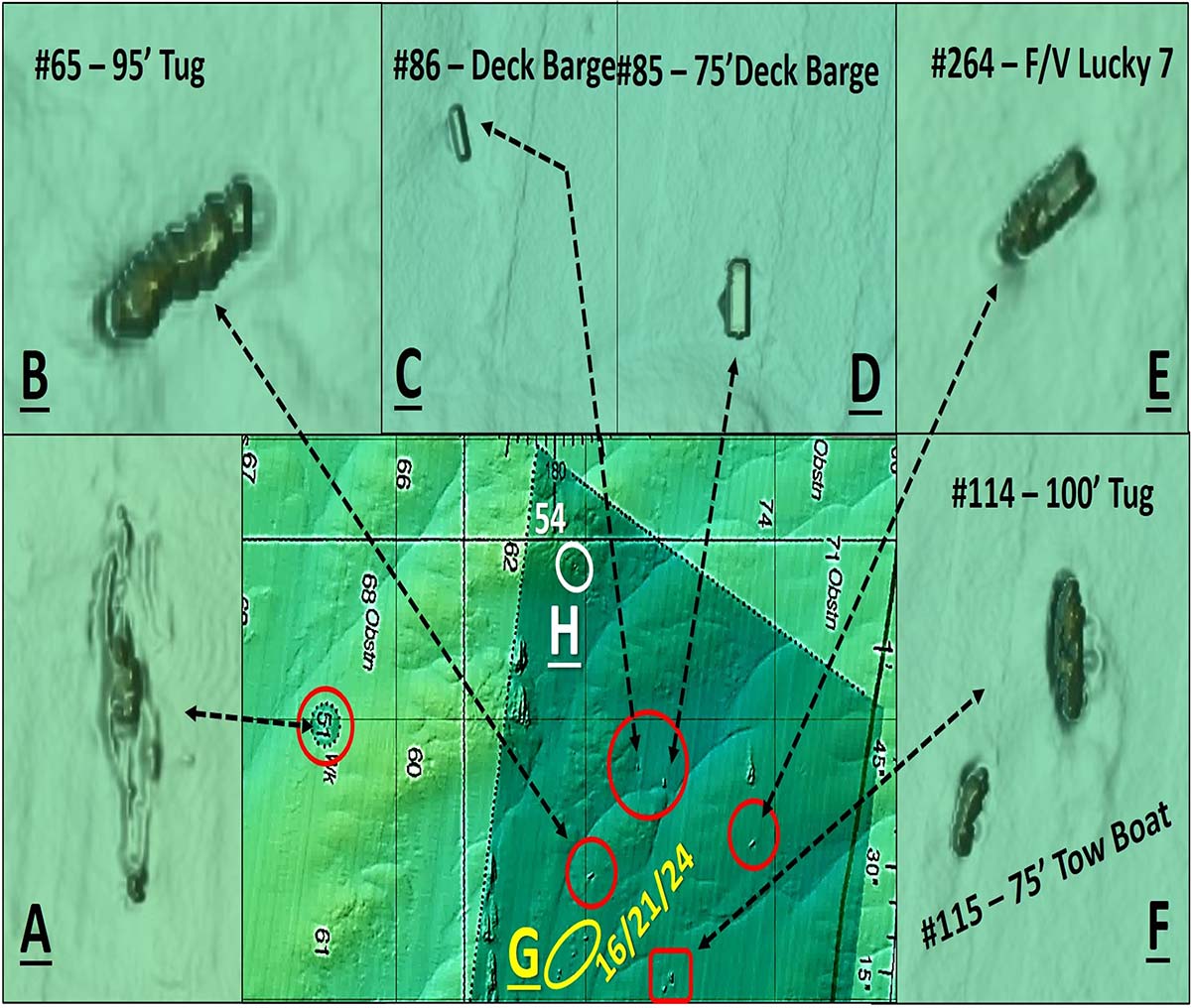

Examples of zooms on a nearby wreck and objects found in the north end of the reef site are shown by CHART 4. Reef identification numbers from the grid and table correlated with the “BAG” image as author-interpreted data. Object “A” shows the nearby wreck. Website njscuba.net identifies it as the steamer Delaware which burned to the waterline and sank in 1898. The website has an extensive write-up, a detailed drawing showing the layout of wreckage, pictures, and a discussion of artifacts.

The NOAA Coast Survey’s Automated Wreck and Obstruction Information System (AWOIS) identifies the wreck as the cargo vessel Cadwalder which sank in 1942, but also reports a position accuracy of 1 mile. The diver report based on actual dives is considered correct. An unidentified obstruction about 700 yards to the west southwest or one of the other unidentified obstructions further west could potentially be the location of the Cadwalder wreckage.

Objects Of Interest

Object “B” is a 95-foot tug sunk as a reef in 2000. There is a 2004 AWOIS entry which reports that this vessel is 85 feet long and rises 25 feet above the bottom. Each image needs to be reviewed in conjunction with other available information to assess what is actually there. In this case, the BAG image presents as a series of stacked slabs laying over like a line of fallen dominoes. However, with two sources specifying a sunken vessel, the slab visual effect is probably caused by pixel size.

Objects “C” and “D” show several deck barges. Object “E” is a fishing vessel. Object “F” is a tugboat. There is a smaller tug nearby as shown. Object “G” shown in yellow is the location of an unspecified number of Army tanks. Object “H” shown in white is the location of where an unspecified number of Reef Balls were deployed. With all that rock and a variety of vessel reefs, Axel Carlson Reef is a powerhouse. It offers some of the best fishing structure in the region.

Both reef sites are inshore, only a modest run back to Manasquan Inlet and protected waters. But, they are ocean reefs. When we push the limits of safe boating and fishing, Mother Nature often pushes back. So, always check forecast weather, sea, and inlet conditions. If unfamiliar with an inlet or if you have limited inlet operating experience, consider going out with a local charter captain or well-experienced recreational boater to begin building local knowledge. Once out there, if the weather or surface conditions deteriorate, get back in before running the inlet becomes a high risk.

Wayne Young is a former manager of the Maryland artificial reef program for Chesapeake Bay waters. He is the author of “Chesapeake Bay Fishing Reefs: Voyages of Rediscovery” available on Amazon.com. His Facebook page is Chesapeake Bay Fishing Reefs. Charts and bathymetry images are processed screenshots from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Bathymetric Data Viewer.