More than just a striped bass record-holder, Charlie Cinto was a consummate outdoorsman with a heart of gold.

He was one of the rich guys, the class of fishermen that hired the Cuttyhunk captains to guide them on their Cuttyhunk fishing adventures. Or so I thought. I was just a youngster, taking a 19-foot open boat 13 miles across the Atlantic to fish the productive shores of Cuttyhunk and the Elizabeth islands. Little did I know at the time that the man in question was an iron worker, and along with his friend, Russ Keane, worked overtime and side jobs to pay for the two-man charters that cost the princely sum of $55 to $60 at the time.

I always kept a low profile and seldom walked the docks, but on one occasion while I was tied up to the pier to get a block of ice from Capt. Don Lynch to chill my fish I overheard a guide referencing me, “Who owns that boat tied up to Lynch’s piling?” One of the skippers replied it was some kid from New Bedford to which another stated that it was someone who ran over from Sakonnet, to which the first skipper replied, that “anyone who ran that boat all the way from Sakonnet to the Pigs has a death wish.” I slinked off into the darkness.

Charlie Cinto was one of the severely-addicted anglers who required a striped bass fix on a regular basis, so a few extra hours of running the girders paid for his habit. I was to learn that he had a special arrangement with both Charlie Haag and Frank Sabatowski which allowed them to keep half of their catch and take it to market. Charlie later confided that on occasion they sold enough fish at 30 and 40 cents a pound to pay for the charter trip and the gas to run his beach buggy from the fish house to Provincetown and back to his home in Foxboro because that refit Jeep FC-170 cab over that carried the 16-foot Monitor trailer with a refrigerator and aluminum boat on the roof could suck up some fuel.

Over the course of a few seasons we had passed each other on the guide’s dock, usually in the gloom of fog or mid-morning, where we exchanged a nod or a wave, but we never spoke about fishing or how we did or were doing; that topic was one of the unwritten rules that was off limits. One foggy late June evening as we waited for a wind shift to chase the fog he walked over to my boat and asked me if I was using live eels. The wooden cover of the live bait bucket hanging over the side was a dead giveaway; that broke the ice.

He told me that he would love to make a trip for stripers casting live eels but suggested it would be too dangerous to conduct that exercise at the island where he was well known to Captain’s Sabatowski, Haag and Smith. He opined that Sabby wouldn’t mind but that both Smith and Haag would prohibit him from further charters, fearful that he would reveal secret spots or methods, as they attempted to run us down. We laughed about the “secrets” of dragging heavy wooden plugs or Russell Lures on 60-pound wire in the rips at Sow and Pigs, Devils Bridge and Quicks Hole. “You are OK with Sabby. He told us about the night his fares were hounding you to show your catch and you wouldn’t roll back the canvas. He said he thought about asking you to bring him some eels.”

I informed the soft-spoken man that I would be happy to take him slinging eels off Sakonnet, but after almost two years of not being able to make it happen he invited me to fish with him in a Boston tourney where he promised fantastic prizes and great food. I accepted. I don’t recall the Captain we fished with, but we didn’t win anything however his demeanor that day led me to believe that we could get along just fine and that he was a man who understood when someone was pulling out all the stops to put him on fish or just taking him for a ride. God was smiling down upon us on that first pre-dawn outing at Sakonnet a few decades ago.

On his second cast in one of the locations I had named the ‘Two For Five’, he hooked-up to a 20-pound bass and wrestled it out of that chaos of boulders and white water that usually conceded twice as many escapes as captures. Somewhere in a collection of trays there is an old dusty slide of my friend with his signature smile, taken that day with his usual refrain, “I’ll be damned. For a few minutes I didn’t think she was coming out of there.” We kept four stripers that morning and filleted two at the ramp with those fillets destined to feed longtime friends. I believed I could trust him and introduced him to Inger, my elderly Sakonnet weather lady. I deposited a half fillet in her fridge, and she gifted us with two duce of fresh-baked cookies for the road. With the impish grin I knew so well she cautioned, “no flirting with the waitresses at the Commons boys.” The ladies at the Commons and now their daughters had been waiting on me for decades and they really appreciated a piece of fresh fish to take home for supper. Charlie with his wit and flirting became an instant hit.

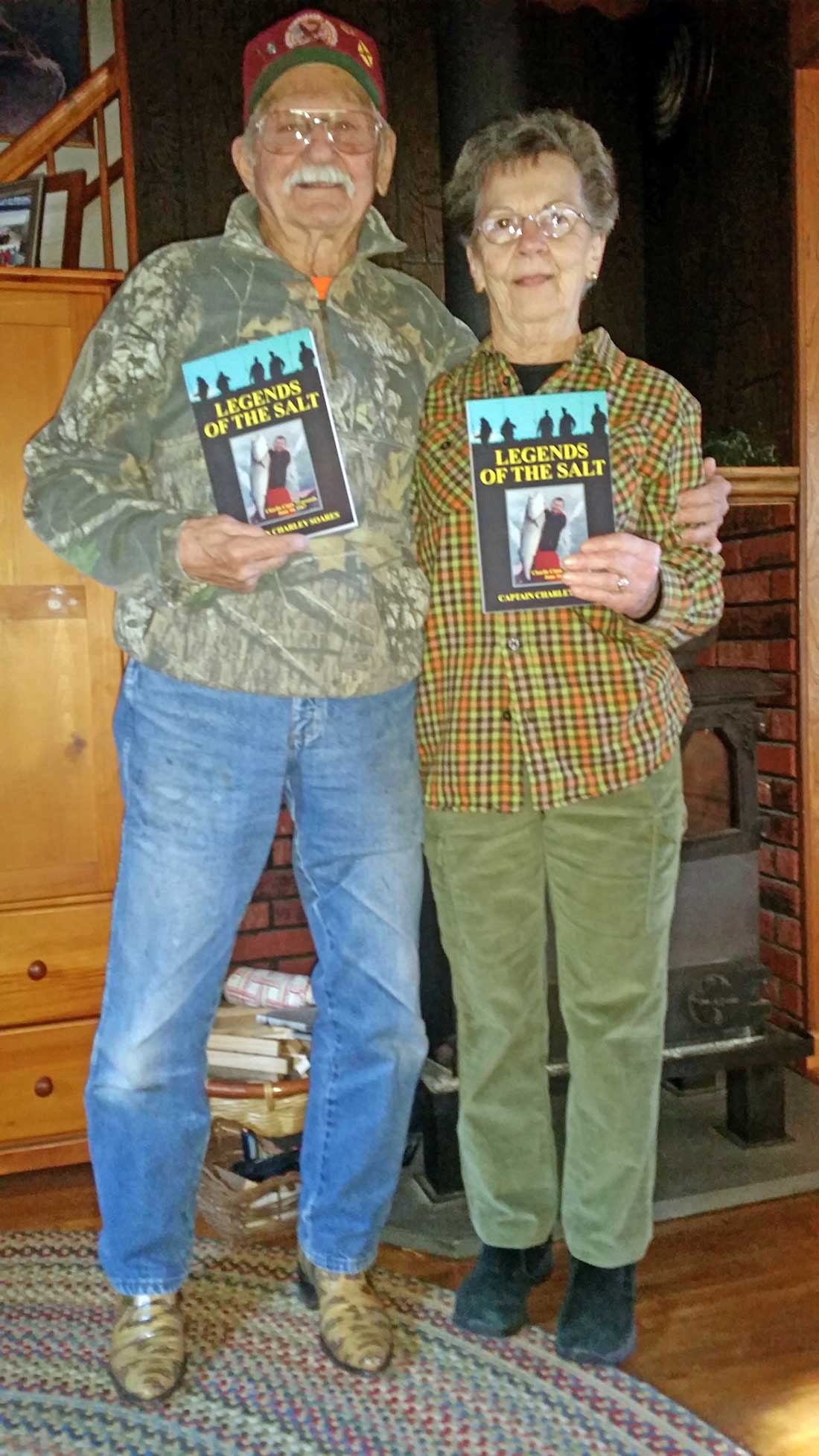

Charles (Charlie) Eric Cinto was much more than a fisherman, he was a loving, friendly, generous and talented man. His initial World Record and now long-standing state record 73-pound striper did not change the man who still enjoyed catching and releasing schoolies in my back river. He has been building and repairing rods, several of which included a fluke rod for my wife as well as rods for me, my son Peter and Grandson Lleyton who became Charlie’s adopted grandson. He met Lleyton 12 or 13 years ago and has been sending him birthday and Christmas cards with spending money ever since. Cinto was a hunter, fisherman and conservationist who was also a travelling man.

As a boy who lost his father at the age of three, by the time he was in school in Fall River he pleaded with his mother to allow him to live on the farm of his maternal grandfather where he spent his summers working as a farmhand seven days a week and loving every minute of it. His sainted mother remarried and went on to deliver a total of 17 healthy children and lived to the age of 94. Early on she began clipping my newspaper columns and saving them for Charlie when he came to visit. He told me his hero was his grandfather, Eric Anderson, a hardworking man who owned a small dairy farm and planted about 25 acres of corn and several other vegetables that he sold to markets and from his farm stand.

That was a joyful time in Charlie’s youth working with and alongside his grandfather, cutting hay by hand and storing it in the same manner in the loft above the cow barn. His grandfather began his work day at 4:30 AM and didn’t go to bed until after 10:00 PM and his favorite treat was a bowl of Nabisco shredded wheat covered in heavy cream from his cows. Charlie made butter, helped to can fruit and vegetables and process meat, eggs and other necessities. He went to a local Foxborough school, and some of his free time was spent in the pursuit of brook trout in a stream that ran through the property and small-game hunting with his uncles on weekends. Those same uncles, namely Harold took him to the Canal and showed him how to fish the eel skin rigs and jigs they poured and crafted on their own. Cinto was well travelled driving to California, Florida and Texas where he lived and worked at various jobs including a printer at a newspaper and various jobs in one of the first supermarkets. In Texas he and his wife camped on the beach (I believe San Padre Island) for days at a time feasting on the numerous fish he caught and only driving into town for supplies. My friend was a man for all seasons.

He worked all types of part-time jobs to put money aside for his hunting trips. One of his most adventurous trips was a moose hunt in British Columbia. He killed a moose at dusk, and he and his ax-carrying guide cut out the tenderloins and backstrap and headed back to camp, intending to return at first light to dress the big animal out. They cleared a rise above the kill and found a grizzly feeding on his trophy. The bear rose up and charged as Cinto lowered his rife and fired one un-aimed, point blank shot that stopped the bear a few feet from his boots. A full body mount of that bear, the moose, a caribou and a mountain goat, along with the mount of his 73-pound striper, are displayed in his living room. Charlie Cinto built wooden lures, jigs and eel skin rigs in the shop attached to his home. During the winter months he worked 10- to 12-hour days crafting fish-catching lures and biding his time until the fishing season arrived.

Charlie Cinto turned 91 on January 5, 2020, and then died unexpectedly on January 25, 2020, a few days after visiting and having lunch with us. Charlie Cinto was a lovable man who after landing a fish or saying farewell before he left our house to head for home would throw his arms around me and say, “I love you man.” I miss those hugs and the thoughtful man who bestowed them. Good bye dear friend, until we meet again on the opposite shore.