Summer creek smallies on the fly.

As we move toward the quarter mark of this century, feast or famine is the new normal for river flows. There’s either too much water, or precious little of it. Given the choice, I’ll take more over less. But that decision’s not up to me. Mother Nature will do what she’s going to do, and if you’re an angler, it’s up to you to adjust to those challenging conditions.

The year 2020 was a challenging year for smallmouth fishing, not only because the pandemic – there were more anglers competing for fishable water than in previous years – but also because southern New England was gripped by drought. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, through late summer my home state of Connecticut experienced abnormally dry to extreme drought. None of those classifications are good for healthy rivers – or water temperatures.

Still, I am addicted to fishing for smallmouth bass on the fly. I knew the fishing would be challenging, but I also recognized it as a terrific opportunity to learn more about how to catch smallies in low, warm water. So, fly rod in hand, I put in some serious time on my favorite rivers. What I learned will help you catch more bass, whether you’re fly or spin fishing.

Timing Is Everything

Everyone wants to catch fish – but not at the expense of fish mortality, especially since most freshwater bass fishermen practice catch and release. What’s more, when you fish for smallmouth stress can have a tremendous impact on the bite. So it makes sense to fish at a time when it’s not only less stressful for the fish, but also when they’re most likely to be on the feed.

While smallmouth bass prefer cooler water, they can withstand habitat warm enough to fry a trout. Still, I don’t like to fish for smallies if the water is 80 degrees or warmer. The good news is that even in extreme low water conditions and scorching summer heat, it is possible to find water that is in the summer smallmouth acceptable range of 69-79 degrees.

You don’t need to be a hydrologist to reckon that on hot, sunny days, the water temperature will spike sometime in the late afternoon. There are ways you can cheat this. Look for water that is located in a valley or ravine, one where the sun begins to hide behind the mountains and hills that surround it. Shade is your ally. These locations will begin to see a drop in water temperature sooner than areas that are bathed in full sunlight.

As evening arrives, smallmouth will become more active. There comes a point near darkness where the bite tends to shut down; this is a good time to plan your next assault, which should be the next morning, from pre-dawn into early daylight. This is when water temperatures will be at their lowest. Be prepared for savage strikes and very aggressive fish. The morning bite will often last well past sunup.

Location, Location, Location

As is the case with timing, where you fish will influence your success. I’ve learned that in low, warmer water, smallmouth will seek out deep-water refuges. It’s that primal survival instinct: where can a fish go where it will find hospitable water temperatures, food, and cover from predators? (Do not underestimate the importance of this last one. Like smallmouth, birds of prey are opportunistic feeders, and they will stomp any fish foolish enough to venture into slow-moving shallows in broad daylight.)

Places with structure should also be on your radar. Look for: downed trees and submerged logs, which provide cover and are an ideal lair for ambush predators like smallmouth. Deeper riffles that offer cover, current, oxygenated water, and a steady supply of food. Pocket water and boulder fields. Most of all, look for fishable locations that are near deeper water. Remember, in lower light, smallmouth will venture into shallows to feed. If those shallows are close to deep-water daytime cover, your odds of hooking up improve exponentially.

Topwaters

There are few experiences in fishing that pump your adrenaline harder than seeing your quarry crush a topwater bug. One of the biggest lessons I learned last summer was that when it comes to topwater presentations in low, clear, warm water, less is more. That is, I focused less on stripping, popping, and waking my fly, and relied more on the smallmouth’s primal attack urges – and the built-in bite triggers and profile of the fly. Poor smallies! Even in harsh conditions, they just can’t keep themselves from attacking something they think is food.

I got the idea for this more passive presentation style from an article I read on spin fishing for bass with poppers. The concept is simple: you let the popper hit the water…and you do…nothing. You don’t introduce any motion to the bug until the ripples from its impact dissipate. Even then, you don’t start cranking it across the water. You simply give it a little twitch, just enough to remove any doubt from any creatures below that this is indeed something that is alive and looks good to eat.

My experiments began with the Gartside Gurgler. I knew from using this pattern for striped bass that fish would hit it during a passive presentation. Smallmouth were no different. Then I came across a surface bug that goes by the name of Ol’ Mr. Wiggly. That pattern changed my summer.

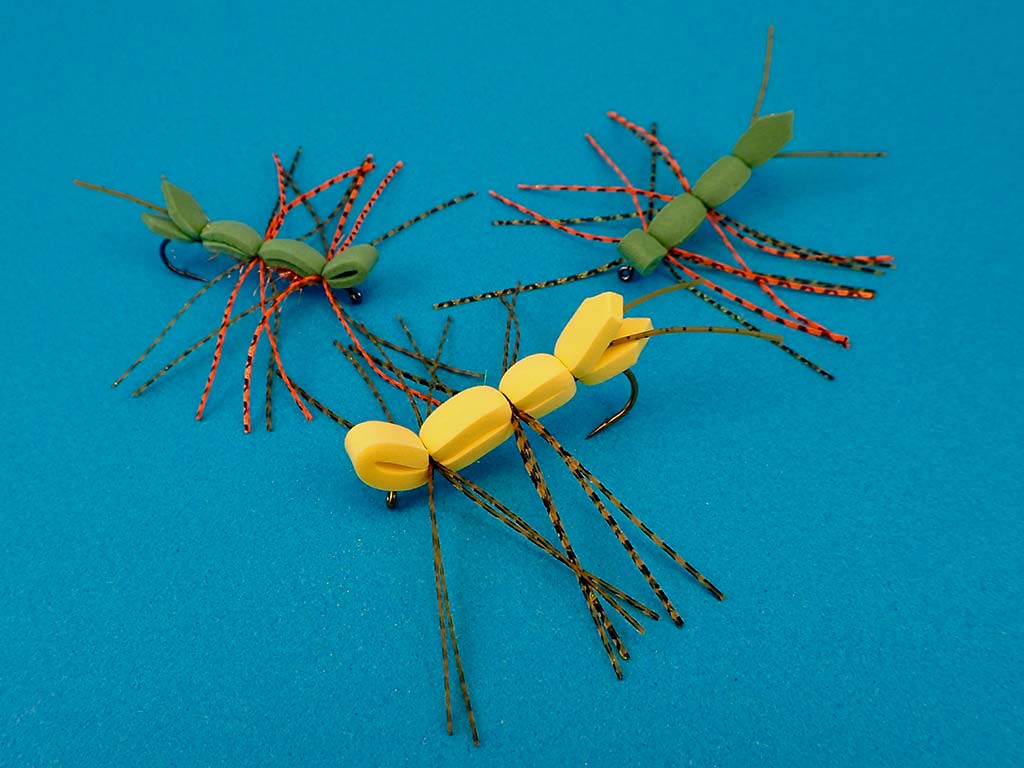

Wigglies, and their variants, resemble a giant Chernobyl Ant. It’s a ridiculously simple concept: a little flashy dubbing on the bottom, a double layer of thin foam lashed to the hook on top, and several sets of wiggling rubber legs and tails guaranteed to drive any smallmouth out of its tiny mind. You fish a Wiggly on the dead drift, just like a dry fly, and if you twitch it, you’re supposed to move only the legs. I took great delight in watching bass after bass smash this fly, even in areas where there was barely any flow or surface activity. Here’s a bonus tip: try a bead head nymph or micro streamer dropper. If the bass are inclined to feed subsurface, the Wiggly serves as an excellent strike indicator.

I tied my Wigglies with white, olive, yellow, and black foam bodies, and found no correlation between color and catch rate. As later afternoon transitioned into evening, I preferred the yellow body simply because I could see it better.

Running Drys

The protein payoff tells us that it’s ideal for a fish to get a bunch of calories in a single serving. That’s why streamers and plugs work so well. But, just as we will sit and munch on a bowl of chips, bass will key on little stuff: mayflies, caddis, midges, and more. It’s an almost universal truth in fishing that a fish will focus on the most readily available food supply, especially if that food is present in numbers and is being delivered to them on the conveyor belt known as current.

If you’re fishing low water in low light, look for the tells of bass feeding on insects. That includes everything from delicate rise rings, to more urgent, splashy takes that indicate that the bass are attacking emergers. You can still tempt bass with more traditional streamers, but you may be surprised to discover that they want nothing to do with a stripped fly.

The famous White Fly hatch on the Housatonic River provides exactly that situation. When the “summer blizzard” is going off, good luck catching a smallmouth on a streamer or popper. Dry flies, on the other hand, are money, and most nights all you need to do is pick out a rise ring and present to that bass. You can catch multiple dozens of smallmouth if you come across such a surface feeding frenzy.

This is a great time for you to retool your dry fly box for smallmouth. You should have plenty of larger patterns, say from size 8 to 12. Keep it simple: Stimulators, Adams, classic Catskills-style dries, White Wulffs, Usuals, Elk Hair Caddis – all of these work. If you’re tying your own, try a few on 2x strong hooks. They won’t float as well as a 1x fine, but you won’t suffer the heartbreak of the straightened light wire hook on a trophy bass. You should also go heavier on your tippets. Gossamer fine tippets and Micropterus dolomieu do not play well together. I’d suggest a minimum of 4x, or a strong, reliable nylon like Maxima 4-pound test. Even with these thicker tippets, you can still achieve a perfect dry fly drift if you lengthen your leader system to 12 or 15 feet.

Get Deep

I spent so many years having great success catching smallmouth on streamers, surface bugs, dry flies, and even wet flies, that it never occurred to me to try nymphing for them. As I learned last summer, not nymphing was a huge mistake.

I came around to smallmouth nymphing via inspiration and desperation. The inspiration part was just simple logic: if smallmouth will readily take a small, weighted crayfish fly jigged along the bottom, wouldn’t they also take a nymph? And, if they are so eagerly feeding on insect life on or near the surface, wouldn’t they be chowing down on the same bugs along the bottom? The desperation influence was also simple reasoning. I was fishing a very long, deeper run that I knew held smallmouth.

At face value, it was the deepest stretch of water for several hundred yards. I wasn’t catching anything on streamers or surface bugs, even as late afternoon transitioned into evening. The bass have got to eat, I reasoned, so I tied up a two fly nymph rig with a 2-inch weighted crayfish pattern on point and a bead head Pheasant Tail as the top dropper. It wasn’t more than a couple casts when my indicator dipped. I set the hook, and I immediately knew it was not a rock that was causing the rod to thrum in my hand. It was a smallmouth, close to two pounds. He’d taken the Pheasant Tail. I spent the rest of the session cackling with delight as I hooked fish after fish.

The conclusion drawn from the nymphing experiment was clear: I was simply making it easy for the smallmouth to feed. In low, clear, warm water, they were unwilling to chase a fly or rise to the surface. But they were perfectly content to eat if the food was brought them. You could do the same kind of thing with a spinning rod, throwing a small jig head soft plastic, and then bouncing it along the bottom.

The most successful football coaches are the ones who are able to make the correct adjustments at halftime. It’s the same thing with fishing. Figure out how the smallmouth are reacting to the conditions. Adjust what you’re doing to how they want to feed. Do those things and you’re going to catch a lot more bass.

Steve Culton is an outdoor writer, speaker, guide, and fly tyer who lives in Connecticut. His website is currentseams.com.