Jesse York passed away at 76 last year at his home in Atlantic Beach, leaving behind a distinguished record of fishing achievements—but he actually lived on “borrowed” time for over 37 of those years after a near-fatal boating incident on the Fourth of July, 1980.

Though I grew up just a few miles away in Merrick, along the south shore of Long Island, we never met until I worked for the Garcia Corp. in Teaneck, N.J. as director of field testing for their fishing products during the 1970s. Jesse was looking for a speaker at a meeting of his Atlantic Beach Rod & Gun Club, and after that winter presentation he invited me to fish for sharks with him the next spring on his Compass Rose, which was one of seven Compass Rose boats he owned over the years.

Those were still the early days of sharking along the south shore when there wasn’t much sophistication to the sport. Just run 10 to 20 miles offshore starting in June and begin drifting while chumming by hand with ground bunker mixed with sea water in a large bucket. There was no consideration of water temperature or structure as long drifts produced a good mix of blue, brown (sandbar) and dusky sharks plus usually at least one shot at a mako. Threshers were unheard of back then. Bunker and mackerel were carried for bait, but we were also able to pick up live ling and whiting with bottom lines during the long drifts. Though all sharks were boated at first in those early “man against man-eater” days, Jesse soon joined Jack Casey’s shark tagging program at the Sandy Hook Marine Lab and became an avid tagger.

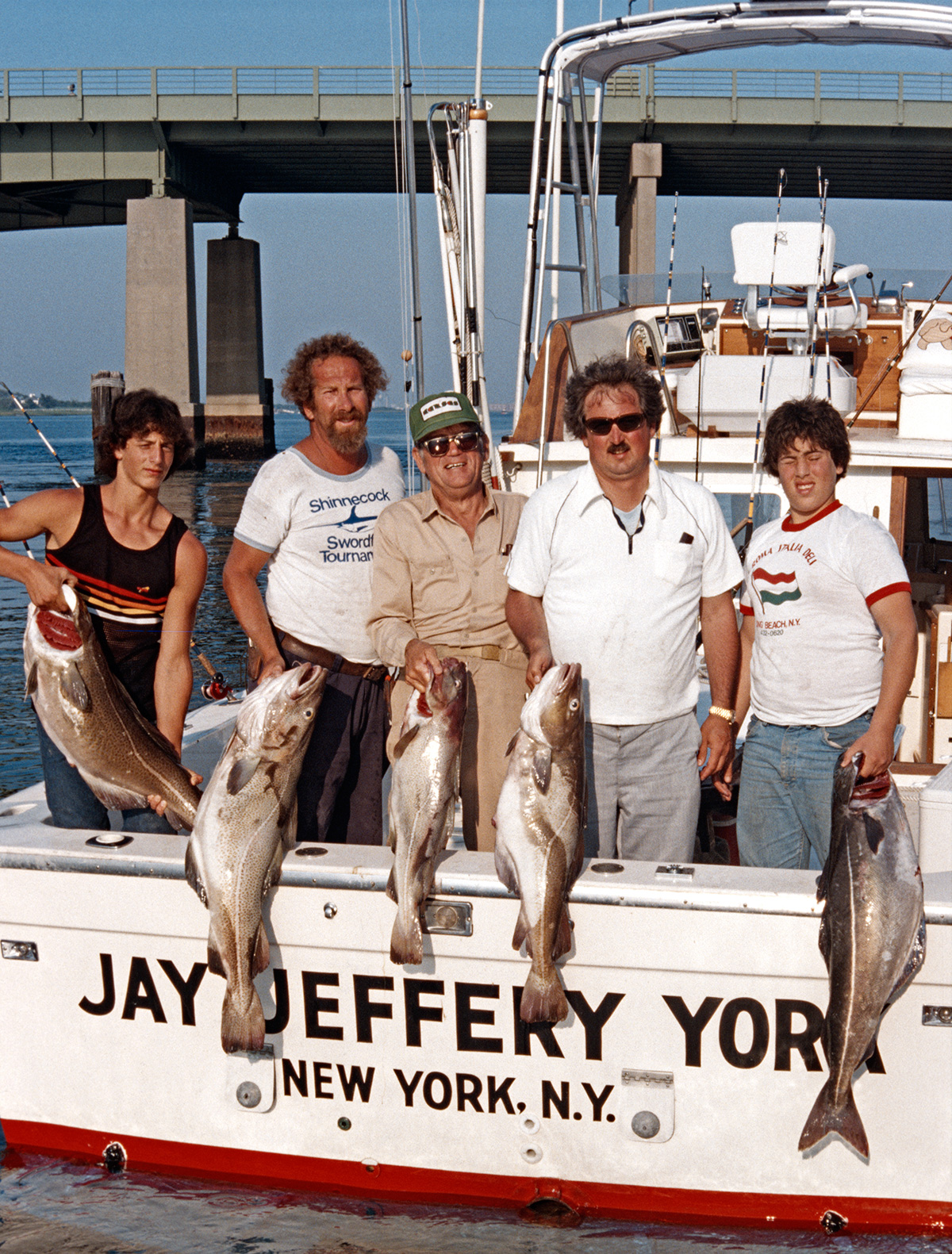

However, the primary objective of that Fourth of July trip was cod and pollock on an offshore wreck—the Virginia. It was also on another boat, a 35-foot Luhrs powered by a Detroit 871 engine, which had been used as a commercial vessel before York bought it cheaply, had a lot of work done to it, and named it after his son – Jay Jeffrey York. It was only a 12-knot boat, but that was plenty of speed for the 3-1/2-hour run in the thick fog we encountered that morning. The boat was outfitted with radar, which was unusual for sportfishing boats of that day.

The radar was an old Decca with a rubber hood into which you stuck your head to be able to spot targets from among all the background clutter. Naturally, that didn’t provide the continuous readings skippers are now used to getting with a glance at an open screen that indicating a tug and tow as two objects moving on the same course and speed. Also, it turned out that the old radar hadn’t been adjusted properly. The crew that day included Jay York, his friend Richie Applebaum, Sid Alter and private boat captain Hy Vogel. I sat on a bucket in the stern shucking clams, while the others were in the cabin running the boat and checking the radar.

We hadn’t been running as long as I expected when the boat was suddenly shut down. I thought that was strange as the technique was to slow the boat near the loran reading, which wasn’t that reliable in those days, in order to search for the wreckage. As I swung around to look forward I saw something that was burnt into my memory forever – a bright yellow Sunoco sign going across our bow!

I moved to the starboard side and watched a tow line come under our bow and move astern, as we still made headway, until the cable got to the struts and stayed there. Jesse remembered he had put in an extra bank of batteries and an emergency starter switch over the winter, and was able to restart the engine. With twin screws we could have backed off, but the single screw just kept swinging the stern back to the tow line.

Though there was no visibility, we knew what had to be on the other end of that tow line! Other than passing out life preservers and sending S-O-S calls, which weren’t likely to be heard on the short range VHF, there appeared to be only two choices: jump in the water now and try to swim out of the path of the barge while being left to float far out to sea with little hope of rescue, or wait for the inevitable collision and hope to survive it while possibly having some wreckage to hang on to.

I was surprisingly calm and still considering my options as a huge barge loomed out of the fog. Jay was only 13, and didn’t know what to expect when he first saw the big wave being pushed by the vessel.

Alter then played a desperation card. He revved up the engine before slamming it into forward. Fortunately, the tow line was hawser rather than cable—and we jumped free as the prop cut it!

After moving out of the path of the barge, we then had to stop and make sure we still had the bottom of the boat. Amazingly, we didn’t seem to be taking on any water. The boat was running a little rough (Jesse had to replace the bent shaft and prop after returning.) but we were intact.

After escaping what seemed to be sure death, any normal person would carefully limp back to port and kiss the ground, but Jesse York was no normal person—he was a fisherman! He headed the few more miles to the Virginia without anyone in the still-dazed crew objecting.

As we were moving around the Virginia before anchoring, the tug boat appeared out of the fog with the skipper outside the wheelhouse using a bull horn to ask us if we’d seen a barge. Jesse told him we hadn’t, but that confirmed the fact that if we’d been hit there would have been no hope of rescue. They had no clue we’d ever been on their tow line, and never would have looked for us if we’d been hit by the barge. When we cut the tow line, the tug had to virtually fly out of the water with all that towing weight gone. The crew were so out of it that they couldn’t even find their barge that had been only a half-mile behind them.

Furthermore, there would have been little hope of rescue even if there was wreckage to hang on to unless some spouse or friend had been told where we had been headed as the Coast Guard wouldn’t have had any idea where to look when we never showed up that night. It was a lesson for everyone on even the most routine boating trips.

We ended up catching about a dozen cod to 35 pounds and a 30-pound pollock. Jesse fished for sharks and broke off one on a 6/0 with 50-pound line after almost being stripped. Not a bad way to finish a day that had almost resulted in our deaths.

There were many good days I enjoyed with Jesse, especially when giant tuna first returned to Massachusetts, and he had a captain run the Compass Rose III up to Provincetown in September, 1971. During the first day, the skipper ran to Stellwagen Bank and started a drift while deploying a 130-pound class rod with a float directly above a 15-foot heavy wire leader and a herring hooked through the tail. He broke a couple of herring in two and threw them in the water to attract giants. It took only 11 minutes before a tuna made a mistake and took that herring hanging in clear sight alongside the boat. Try to hook a giant that way these days.

Veteran tuna captain Oscar Amoruso, of the Marlin at Atlantic Beach, kept a 519-pounder to enter in the Atlantic Beach Rod & Gun Club’s yearly contest. The export market hadn’t been developed as yet, and giants weren’t worth anything at that time, so Oscar’s tuna was shipped to the Fulton Fish Market for pennies. The fish house wouldn’t sell us bait the next morning until we allowed them to dump the head and guts in the cockpit for disposal at sea. After that we only released fish! We tagged six giants and lost others that trip as Jesse, his brother Judd (who preferred bottom fishing), Harry Ross and I joined in the action over two more days of fishing.

Jesse was also among the pioneers of Hudson Canyon fishing, though he usually sailed on bigger and faster boats with Atlantic Beach Rod & Gun Club members, especially with Fred Hill on his Four Queens. During two-day trips in those early days we ran to the canyon and trolled all day for tuna before making a couple of drifts for tilefish at the edge—and then anchored on the flats to chum for sharks at night and concluded with canyon trolling the next morning. It was some time before word spread about anglers who tied onto lobster pot buoys in the canyon at night to chunk yellowfin tuna and swordfish in the dark.

Jesse suffered from a host of physical problems during his last few years, but was very proud to leave behind his son Jay as an even more accomplished fisherman who spent years rod-and-reel commercial fishing for giant tuna before settling down as a family man in Jupiter, FL with his Mystic Rose charter boat out of Castaways Marina. As noted in an article I did for The Fisherman a few years ago, I was able to join Jay on a last trip for his father, who could hardly get aboard the boat at the time, but enjoyed catching snappers, groupers and other Gulf Stream species with his son who sports a memorial tattoo for the man who nurtured his lifelong passion for fishing.