Predator fish have only two purposes in life. One is to reproduce and the other is to eat and get big, the latter dominating their behavior for 12 months a year. This is known by all anglers as evident by the universal chant “Find the bait, find the fish” said every time clutter appears on our fishfinder. We all know the mantra but do we really know the bait? The sad reality is that very few people do, focusing all of their research on the predator while neglecting the most critical component of its life, the food source.

If you look in the mobile phones of every charter captain and commercial angler in Rhode Island, you’re guaranteed to find the name “Pogy John” in every address book. When the bite gets tough and fish refuse to eat artificial lures, The Legend of Pogy John is clearly seen as a line of boats wait their turn to visit their savior. New England born and bred, John Donahue has over 35 years’ experience commercial fishing, starting as a teenager fishing with his grandfather and father. He knows the water and more importantly knows the bait better than anybody else in the bay. Each morning John catches live bunker, which he sells to trophy hunters who target big stripers. Every day the success of many charters depend on Pogy John’s ability to find and catch bunker.

“Each year they start out in open ocean and begin to work their way up into the Bay,” stated the Captain. “I typically won’t chase pogy until they start coming in as they’re too hard to pinpoint in open water. In Rhode Island it’s typically early to mid-May. Guys living south in NY-NJ, it’s often a month or so earlier.” Fortunately, this early season is when most anglers are focusing on catching blackfish so a market for live pogy doesn’t exist. “The bait usually come in first and the striper won’t be far behind them. They time each other well.”

Knowing where to start is one of the most difficult parts of catching bunker. “A good social network is critical. I’m fortunate to have many contacts who tip me off when they see a pod of bait so I’m constantly receiving information.” said Donahue. Even when he’s on a consistent school for days, he welcomes information about new areas. “I’ve seen entire bays loaded, only to return the next day and find none. Not a single bunker for miles when you couldn’t avoid them the day before. It’s crazy. I’ve had to launch my boat four to five times a day in different areas to get back on them.” The more information he gathers from his network, the more he protects himself when one school disappears.

When in an area that should hold fish, he starts looking around for signs of life such as bunker flipping on the surface. Most of the time it’s not that easy and he’ll watch for other clues. “Being attentive to nature is a big part of it. A single osprey or cormorant will give up the location of a giant school. Don’t overlook even a single bird. It doesn’t have to be a giant flock to tell you that baitfish is around.”

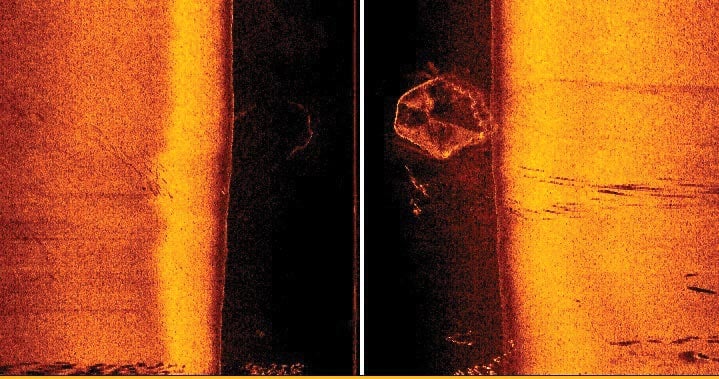

“If they’re not on the surface, you have to use technology to find them. I bought the first side imaging sonar ever made, the Humminbird 997 back in 2008,” a time that coincidentally lines up to the start of his bait business. “I had a huge advantage being able to scan way out to the port and starboard sides and not limit myself looking straight down with regular sonar. Humminbird’s always had the best side imaging and I’ve continued to upgrade over the years.” Pogy John’s current boat is outfitted with Humminbird HELIX 9s using high frequency MEGA Side Imaging.

Understanding his electronics and making proper adjustments is critical to John’s success. “When I don’t know where they are, I start by opening the range on my side imaging to look a long distance, between 160 to 200 feet on each side. The image might be somewhat blurry but I’ll make out the edge of a school if they get within there.” For reference, when John’s range is set to 150 feet, his sonar is viewing a full 300-foot swath, covering a football field underwater. “Once I know where they are I drive closer to the school and shorten the range to 80 to 100 feet, which brings out the detail. With MEGA Side Imaging, you can almost count the number of bunker in a school.” The captain makes note of the school size and the direction of travel. “If it’s a small isolated school, I won’t throw on them unless nothing else is around. It’s important to use your electronics to size up the bigger pods from the smaller ones.”

To catch bunker, the captain uses Fitec cast nets (www.castnets.com) in a variety of sizes varying from 8 to 14 feet in diameter with 1.5 pounds of lead per foot of radius. Conditions and fish behavior determine which size he chooses. “When they’re sitting still in open water, I’ll use an 8- to 12 footer. The days where they’re deeper and in small schools moving fast, such as overcast days with a northerly wind, I step up to a 14-footer. The simple rule: The deeper the water and the harder they are to catch, the bigger the net.” Smaller nets are used whenever possible as it’s quicker to throw and won’t wear the angler out when multiple throws are needed. Small nets are ideal in tight areas that include moored sailboats and other pieces of cover for bunker to hide. It’s not uncommon for the captain to brush up on the sides of these obstacles to create noise and scare the bait out from hiding. They often expose themselves for only seconds and being able to see where they are and be quick with a cast net is crucial.

In open water, John uses his outboard to corral bunker. Monitoring wind, tide and direction they’re travelling, he drives alongside the school with his net ready. As he approaches the front of the pack, he sharply cuts the steering wheel in front of the fish creating a barrier of bubbles from outboard exhaust. As he circles around tightly, many of the frightened baitfish resist swimming through the bubble trail and get grouped tightly for a well-placed net throw. Days where they’re docile the smaller net is used. Days where they’re active and swim straight through the barrier, more throttle and a larger net is needed.

John’s system for keeping bait alive is simple. “I’ve got a large barrel in the boat with several pumps feeding it. The most important part is having freshwater constantly circulated and added. If you don’t the bait will end up polluting its own habitat [going to the bathroom] removing its slime coat and killing itself. It’s also critical to aerate the water and keep the environment relatively stress free if you want your bait to be lively over the course of a day.”

Very few anglers take catching bait as seriously as they should. It’s common to hear of boats wasting half their day trying to locate and catch a dozen bunker. In many cases hunting bait is more difficult than catching your intended species. Despite all of this, we continue to neglect learning about its migration and honing our skills to catch it. It’s the driving force behind every decision a predator fish makes and so few people understand it. Hopefully this article gives you confidence in finding and catching your own bait. If it seems like too much work, just remember the secret all charter captains in the Narraganset Bay know, take out your cell phone and call Pogy John.