It’s go time once again along the Striper Coast, but go where?

Striped bass migrations, movements, and population dynamics have fascinated anglers since the first surf fisherman made a cast into the wind and felt “the jarring rush of a striper” as Frank Stick put it exactly 100 years ago in Van Heilner’s book The Call of the Surf.

In their seminal tome Fishes of the Gulf of Maine published in 1953, Henry Bigelow and William Schroeder also noted that “no phase of the striped bass life history arouses as much discussion among fishermen as their migration.”

Along the U.S. Atlantic coast native stocks of striped bass occur from the St. Lawrence River in Canada to the St. Johns River in Florida; however, the area from approximately Cape Hatteras, North Carolina to Cape Cod, Massachusetts, known to anglers as ‘The Striper Coast,’ is the center of abundance for striped bass.

The Big Four

Currently four major, geographically specific spawning grounds for striped bass along the Atlantic coast are recognized – the Hudson River, the Delaware River, the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries, and the Albemarle Sound-Roanoke River estuary. Spawning typically occurs in freshwater portions of these systems from April to June, earliest in southern spawning grounds and later moving north.

After spawning many individuals leave these spawning areas and comingle as they move north and east along the coast to feed off the mid-Atlantic and New England coast in summer. Some fish stop and spend long periods of time as summer residents in areas of suitable habitat along the way and only make minor localized movements during the remainder of the summer while others move around feeding in multiple areas for shorter periods. In either case, for the most part, summer is spent foraging and growing before eventually returning south and west to wintering areas in fall and subsequently returning to natal waters the following spring for spawning.

Tagging studies have revealed that some stripers return to the same locales where they spent the previous summers. Some striped bass even make their way into non-natal waters in summer and remain there during fall and winter until moving south the following spring. The annual return of individuals to the same location provides evidence of what scientists refer to as site fidelity. However, while some individuals show a high degree of site fidelity and annually maintain summer residency in a particular river, estuary, or coastal region, others exhibit different patterns of distribution and abundance in different years.

In fall as water temperatures begin to decrease, striped bass that have spent the summer in feeding habitats begin their annual movement to overwintering areas. Early tagging studies established the fact that some stripers winter in nearshore ocean waters from around Sandy Hook, NJ and Cape Lookout, NC from November to March with a substantial annual winter aggregation of primarily larger striped bass overwintering off Cape Hatteras, NC. These ocean aggregations are typically comprised of fish from a variety of spawning areas. Other coastal migrants overwinter where spawning occurs including the Hudson River, the Delaware Bay and Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries, while some overwinter in rivers and bays along the coast from New Jersey to North Carolina.

For example, small stripers are known to move into rivers and bays along the New Jersey coast to overwinter including Toms River, Barnegat Bay and Great Bay-Mullica River, where they typically remain until spring. Available data suggests that the source of striped bass in these non-natal rivers and estuaries along the New Jersey Coast is likely the result of movement of fish from the Hudson River and Delaware Bay stocks into these waterbodies rather than providing evidence of these waters supporting spawning to any degree.

Tagging studies have also documented that striped bass overwinter in the Hudson River and indicate that many of the fish overwintering there are of Hudson origin although a small proportion of Chesapeake Bay fish also spend the winter there. Tag returns also illustrate overwintering of Hudson-origin striped bass in coastal and estuarine waters south of Cape May, NJ. These studies also found that striped bass of Chesapeake origin overwinter in tributaries, embayments, and coastal waters ranging from New Jersey to North Carolina. In addition, the open Chesapeake Bay serves as an important overwintering habitat for members of the Chesapeake stock along with fish from other regions as well. There is also evidence from tagging studies that there may be migratory individuals from southern spawning grounds that linger and spend winters in more northern inshore locations such as the Thames River, Connecticut, Long Island Sound, and other areas of suitable habitat.

On The Move

The factors motivating striped bass migratory behavior as well as shorter-term local movements are not definitively known although the presence of adequate prey, favorable environmental conditions and other optimal habitat attributes may all play a role. To sort out information on striped bass movements, residence times, site fidelity and habitat use in both natal and non-natal rivers and estuaries, scientists have begun to use acoustic telemetry technology. Acoustic telemetry works by implanting transmitters in individual fish that emit a unique signal (ping). When a signal or ping is detected by receivers deployed throughout a study area the transmitters unique ID is recorded with date and time, providing a record of each visit to a particular location. Over time, the information produced in telemetry studies will provide a more complete picture of the subtleties of striped bass life history.

The timing of when striped bass join the coastal migration has been shown to vary by age and sex. As early as the 1930s, researchers felt it was probable that striped bass between the ages of 1 and 2 years old tend to remain in or close to their natal river systems and, as they grow older begin to expand their range of movements, first within their natal systems and eventually along the Atlantic Coast. Many studies since that time have confirmed that young striped bass remain in or near the tributaries or embayments where they were spawned for up to three years before joining the coastal migration.

There is also evidence from tagging studies that female stripers typically tend to leave natal spawning systems and join the coastal migratory stock while males are more prone to stay in these systems rather than migrate into coastal waters. In fact, in the 1950s researchers suggested that approximately 90 percent of the striped bass moving along the coast into northern waters were females. Recent telemetry studies in Chesapeake Bay provided updated evidence that a substantial portion of the post-spawn striped bass emigrating from the Bay are females with males more likely to remain in the Bay throughout their lives.

As early as the 1940s researchers also speculated that striped bass migratory patterns conformed to the contingent hypothesis since some individuals from regional spawning areas make annual movements along the coast while others form non-migratory resident groups. The concept of contingents of fish that engage in a common pattern of seasonal migration between feeding areas, wintering areas, and spawning areas, was first introduced by fisheries scientists in the early 20th Century.

For example, in the 1950s it was suggested that an upstream and a downstream contingent of striped bass existed in the Hudson River. Tagging studies conducted in the 1960s lead researchers to further propose that there were three contingents in the Hudson – one that occurs in Long Island Sound from summer to fall and moves into the river to overwinter until spawning, then returns to the Sound in summer; one comprised of fish that winter and spawn in the Hudson and move into adjacent embayments to feed in summer; and one consisting of fish that spend the summer in the New York Bight and southern New England, overwinter in offshore waters or rivers and bays to the south and move into the river in spring for spawning.

Chesapeake Bay studies in the 1950s and 1960s indicated that subpopulations or contingents probably existed within the Bay as well as within its associated tributaries where spawning occurred.

More recent studies capitalizing on advances in acoustic telemetry technology and otolith microchemistry have provided new evidence of the existence of contingents within the Hudson River and the Chesapeake Bay. Otoliths are a fishes ear bones and contain pairs of bands or ‘growth rings’ that fish produce annually. Otoliths provide information on a fish’s life history including incorporating trace elements from a fishes surroundings as their growth rings are laid down. By analyzing otolith microchemistry, scientists have been able to relate the ratio of certain elements contained in otoliths to residence and/or movement between different salinity regimes of the waterbodies inhabited by individual fish.

The combination of telemetry surveys and otolith analysis has provided a refined classification of Hudson River and Chesapeake Bay contingents. For the Hudson, results identify an upper river contingent consisting of resident individuals that primarily inhabit freshwater portions of the Hudson for the majority of their life although they make visits to the lower tidal portions of the Hudson River during winter; a middle/lower estuary contingent that inhabits the lower estuary including New York Harbor and western Long Island Sound year round; and an ocean contingent, which is the migratory contingent that inhabits ocean waters and coastal marine environments and makes annual spring excursions into freshwater for spawning. In Chesapeake Bay these studies support the premise of a two-contingent population: a resident contingent that moves between freshwater portions of various spawning rivers to lower reaches of these rivers or into the Bay proper and an ocean contingent comprised of fish that leave the Bay and move along the coast as members of the coastal migratory population.

Mixed-Stock Recreational Fishery

The striped bass recreational fishery along the east coast is considered to be a mixed-stock fishery. Therefore, anglers along the Striper Coast may be encounter fish from any of the geographically distinct striped bass spawning areas during the spring and fall migratory runs. Attempts to make accurate estimates of the annual contribution of individual stocks to the fishery have been going on since at least the middle of the 20th Century.

However, these attempts have been a challenge because the relative contribution from individual stocks may vary from year to year depending on a variety of factors. These include stock size, year class strength, recruitment success, fluctuations in environmental conditions, and harvest pressure as well as abundance shifts that happen during a season as different year classes participate in the migration at slightly different times, in addition to the complex life history of striped bass which is comprised of overlapping generations, fecundity that varies by age, and the different dispersal patterns of males and females.

For example, reports from the mid-1900s identified the Albemarle Sound, Chesapeake Bay, Delaware River and Hudson River as important spawning areas supplying striped bass to the coastal recreational fishery along the Atlantic coast. In the 1970s, the major spawning areas contributing to the fishery were considered to be the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries, the Hudson River and the Albemarle Sound-Roanoke River. By the late 1980s it was believed that the Hudson and Chesapeake were the predominant contributors to the coastal fishery.

In Chesapeake Bay, beginning in the mid-1970s habitat destruction, pollution, and heavy fishing pressure caused a significant decline in striped bass abundance leaving the population with a large number of immature fish which negatively impacted spawning and recruitment. During that same period, the Hudson River population became more important as this population was receiving protection because of strict harvest restrictions placed on all coastal striped bass in the 1980s aimed at protecting the Chesapeake Bay stock and because the Hudson River commercial fishery had been closed due to unacceptably high levels of PCBs being found in their tissue.

In Chesapeake Bay, beginning in the mid-1970s habitat destruction, pollution, and heavy fishing pressure caused a significant decline in striped bass abundance leaving the population with a large number of immature fish which negatively impacted spawning and recruitment. During that same period, the Hudson River population became more important as this population was receiving protection because of strict harvest restrictions placed on all coastal striped bass in the 1980s aimed at protecting the Chesapeake Bay stock and because the Hudson River commercial fishery had been closed due to unacceptably high levels of PCBs being found in their tissue.

In the case of the Delaware River, although it was historically considered to be an important spawning ground and nursery area for striped bass, by the early 1900s the Delaware River was among the most polluted estuaries in the United States. In the 1960s water quality in the river was so degraded as a result of a variety of pollution sources, including raw or inadequately treated sewage discharges along much of the river and its tributaries an annually occurring zone of oxygen depletion had formed a ‘pollution block’ impeding fish movement to upstream spawning grounds. As a result, there was speculation that the spawning population may have been eradicated. This problem was eventually resolved with installation of secondary sewage treatment plants along the river and by the 1990s there was evidence that limited spawning had resumed in response to the improved water quality; however, at the time the source of the spawning population was uncertain.

Several hypotheses have been presented that could account for the origin of the revived Delaware River striped bass population. Assuming that the Delaware River stock became extinct in the 1960s repopulation by fish from other stocks could have occurred. If the spawning population didn’t become extinct, then expansion of a remnant of the original Delaware Bay population could be responsible. It has also been hypothesized that the current Delaware River striped bass are an extension of the Chesapeake Bay stock supported by the transport of eggs and larvae from the upper Bay and Chesapeake and Delaware Canal into the river as well as movement of mature spawners moving into the river through the canal. The current Delaware River population may also be the result of some combination of these possibilities.

In the case of the Albemarle Sound-Roanoke River stock, although historically the population was primarily viewed as nonmigratory with most fish believed to remain in the Sound or nearby coastal waters throughout their lives, some evidence existed to support limited movement of fish out of the estuary and along the coast. By the 1970s and 1980s this stock became depleted as a result of habitat destruction, overfishing, and poor recruitment leading to speculation again that the stock was largely confined to the estuary and associated rivers and that there was little evidence that the stock was contributing to the coastal migratory stock and associated fishery.

However, during the past several decades, more stringent fishing regulations have increased survival of fish to older age classes and improvements in environmental conditions have enhanced spawning habitats. As a result, the stock has experienced increased recruitment and abundance and its age structure has expanded, resulting in mature fish from this area increasing their movements outside of the Sound into the ocean and north along the coast.

Collectively, these studies indicate that the Chesapeake Bay stock remains the major contributor of fish to the mixed-stock coastal fishery along the Mid-Atlantic and New England coasts supplemented primarily by the Hudson River stock especially in areas adjacent to the river including western LI Sound, the New York Bight, and the northern NJ coast. Furthermore, although small in comparison to the Hudson River and Chesapeake Bay stocks, the Delaware River and Albemarle Sound-Roanoke River also make important contributions to the coastal migratory stock and associated recreational fishery.

Future Studies & Understanding

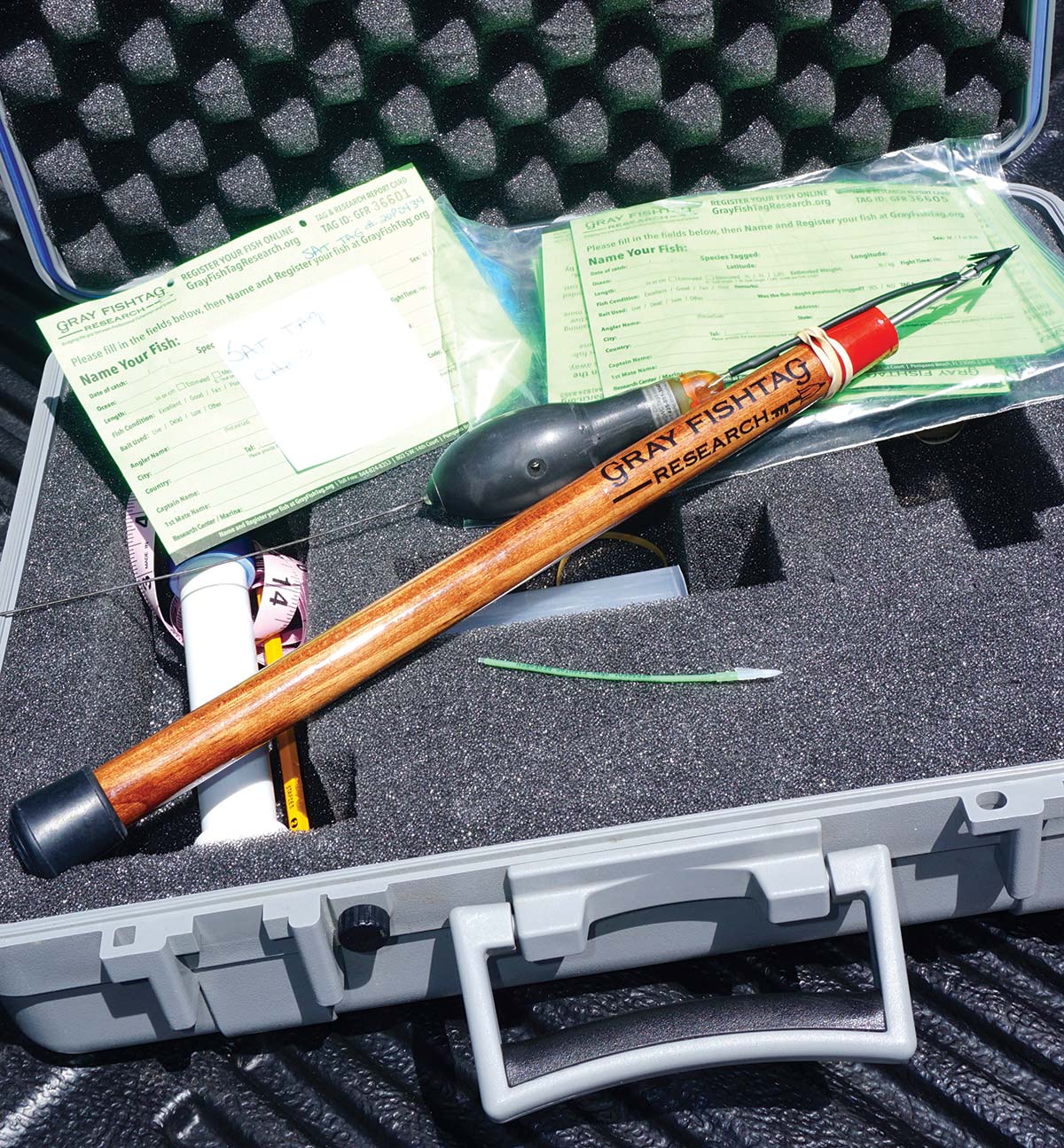

As part of the 2020 Northeast Striped Bass Study presented by The Fisherman and Gray FishTag Research three striped bass of 46 inches or greater were affixed with MiniPSAT devices this season to track their movements over the course of 4 months. Striped bass named Cora and Rona were caught, tagged and released on two separate trips on May 28 and June 3 just east of Sea Bright, NJ, while a third bass off Montauk, NY on July 3, Independence, become the fifth striped bass since 2019 to carry a Gray FishTag Research MiniPSAT device.“The first two tags of 2020 have popped, and the initial results are a little shocking,” said Bill Dobbelaer of Gray FishTag Research. “We were as surprised as anyone last year when those first two tags showed tracking data from deep offshore in the canyons, but the preliminary results in 2020 seem to indicate that a lot more scientific research into striped bass migration patterns is needed in the future.”The MiniPSAT devices used in the Northeast Striped Bass Study incorporate light-based geolocation for tracking, time-at-depth histograms for measuring diving behavior, and a profile of depth and temperature. Tags were set to remain attached to each fish for up to 4 months, but the tags employed on both Cora and Rona have already disengaged and have been feeding the Argos satellite. “The team at Gray FishTag Research is still compiling and scrutinizing the data from 2020, but we hope to have the results published in our November edition,” said Mike Caruso, publisher of The Fisherman Magazine.For more details on the Northeast Striped Bass Study and the preliminary findings of Cora and Rona, be sure to pick up the November edition of The Fisherman.

As part of the 2020 Northeast Striped Bass Study presented by The Fisherman and Gray FishTag Research three striped bass of 46 inches or greater were affixed with MiniPSAT devices this season to track their movements over the course of 4 months. Striped bass named Cora and Rona were caught, tagged and released on two separate trips on May 28 and June 3 just east of Sea Bright, NJ, while a third bass off Montauk, NY on July 3, Independence, become the fifth striped bass since 2019 to carry a Gray FishTag Research MiniPSAT device.“The first two tags of 2020 have popped, and the initial results are a little shocking,” said Bill Dobbelaer of Gray FishTag Research. “We were as surprised as anyone last year when those first two tags showed tracking data from deep offshore in the canyons, but the preliminary results in 2020 seem to indicate that a lot more scientific research into striped bass migration patterns is needed in the future.”The MiniPSAT devices used in the Northeast Striped Bass Study incorporate light-based geolocation for tracking, time-at-depth histograms for measuring diving behavior, and a profile of depth and temperature. Tags were set to remain attached to each fish for up to 4 months, but the tags employed on both Cora and Rona have already disengaged and have been feeding the Argos satellite. “The team at Gray FishTag Research is still compiling and scrutinizing the data from 2020, but we hope to have the results published in our November edition,” said Mike Caruso, publisher of The Fisherman Magazine.For more details on the Northeast Striped Bass Study and the preliminary findings of Cora and Rona, be sure to pick up the November edition of The Fisherman.As noted, scientists have used a variety of methods over the years to expand our knowledge about striped bass stocks and sort out their relative contributions to the mixed-stock coastal fishery. The results of several recently published studies using genetic markers have assigned striped bass moving along the Striper Coast to one of the following groups: the Hudson River stock, the Chesapeake Bay-Delaware River stock, and the Albemarle Sound-Roanoke River stock.

It should be noted that the results of these genetic studies as well as some of the older studies using morphological characteristic concluded that Chesapeake Bay and Delaware River striped bass appear to share a set of common characteristic including DNA variation that makes it difficult to separate them geographically, therefore they currently should be considered together as the Chesapeake Bay-Delaware River Supergroup although the Delaware River’s contribution to this Supergroup is considered to be small in comparison the that of the Chesapeake.

We have applied genetic techniques in our own analysis of DNA isolated from fin clips collected from striped bass caught by members of the Berkeley Striper Club on beaches along northern Ocean County in New Jersey during recent fall runs. Preliminary results from this effort allowed us to place the fish we sampled into three geographic clusters consistent with the classifications identified in the recently published genetic studies mentioned above. Most of the fish we sampled {66 percent} were assigned to the Chesapeake Bay/Delaware River Supergroup, while 20 percent were of Hudson River origin and 14 percent were from the Albemarle Sound – Roanoke River.

As scientific tools and techniques such as acoustic telemetry, otolith microchemistry and genetic differentiation are further refined and applied in striped bass during future migratory runs and in non-natal waters frequented by stripers in summer foraging areas or winter aggregation areas, they will increase our knowledge and understanding of striped bass life history and lead to enhanced conservation and management measures designed to sustain the recreational fishery for the future.

John Tiedemann is Assistant Dean in the School of Science at Monmouth University and Director of the University’s Marine and Environmental Biology and Policy Program. His work over the past 40 years in the classroom and the coastal community has addressed a wide range of marine and environmental science and natural resource management issues in the region, including the 2011 launch of the angler-based research and education campaign Stripers for the Future.