How a little underwater surveillance can change one’s strategic focus on whitechins.

Blackfish, or tautog (or even tog), may not be the prettiest fish, nor do they reach “big game” proportions; but there is something about these thick-lipped, slimy reef-dwellers that encourages obsession in anglers.

I happily admit to being one of those individuals fixated on these fish. From an early age I’ve been fascinated by tautog. There have been a few times when I almost thought I had tog all figured out, only to be vexed by a lack of success under what I thought were optimal conditions.

Over the last several years I’ve made a focused effort to try and better understand tautog. While I haven’t come close to figuring out everything about them, detailed observations from both above and below the surface have allowed me to make at least a little progress towards this goal.

“Fish Eye” Research

Tautog are members of the wrasse family of fishes (family Labridae which refers to those big lips). Wrasses number over 600 species of mostly tropical and subtropical reef fishes found around the globe, with tautog among the northernmost-dwelling members of the family. They share with their tropical cousins a love of underwater structure, but also a sensitivity to low water temperatures; tautog will go into a torpor in temperatures below about 40 degrees F.

In warmer climes wrasses tend to be non-migratory, but tautog undergo seasonal movements to stay within their preferred temperature range of 50 to 68 degrees. This draws the fish into the shallows to feed and spawn in the spring, and drives them back into depths of 40 to 100 feet or more during the winter. It’s during the fall that the fish are at their most active, feeding heavily before cooling water temps drive them back to deeper waters.

While I had long been aware of these seasonal movements of tog, probably the biggest misconception I’d had about them was the extent to which they may move around on an average day. Previously I’d thought of them as being relatively sedentary, setting up in their own little pocket of a structure and barely poking their heads out to nibble on a bait. It is true that tautog will set up home on particular pieces of structure for a time, but I’ve learned that they’re anything but sedentary; they may not spend all of a given day on a piece, or even feed there. Further, they often follow different patterns of foraging behavior depending on the depth and characteristics of the structure where they’re living.

Perhaps the most interesting of these behavior patterns is seen in tog sheltering on isolated shallow water structures such as boulders and small rockpiles. I had long puzzled why the fish in such locations would bite like crazy one day, and seemingly be gone the next. On other days, I would patiently endure a slow pick for hours, and then suddenly have my sonar screen light up with fish and have the bite turn on.

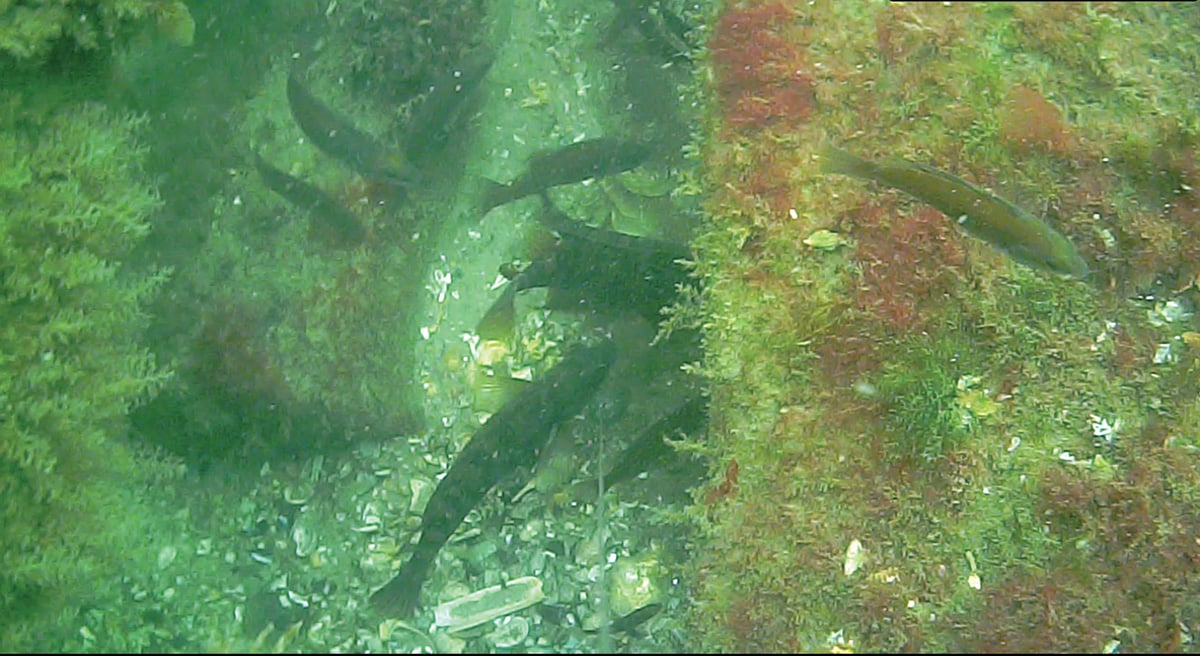

Through a combination of underwater video, examination of stomach contents, and detailed catch logs, I’ve discovered that these fish use shallow water structures as staging areas from which they go on foraging runs of up to at least a quarter mile, then return to their “homes” to rest, digest and sleep at night.

The strongest evidence of this comes from one of my favorite shallow water tog spots, where the fish’s stomachs are almost always stuffed with black mussels, calico crabs and jingle shells, none of which have been visible on any of the underwater videos I’ve shot there. I know this area very well and am aware that the nearest bed of black mussels is about a quarter-mile away. The calico crabs and jingle shells are widely dispersed on the expanse of sand bottom that the togs have to traverse in order to reach the mussels, so are probably encountered incidentally while the fish are coming and going from their home structure.

When I figured out what was going on – that the fish were often simply not on the structure I was fishing for certain periods of the day – my erratic and unpredictable catches made a lot more sense. I was only catching fish in that spot when the fish were home, during their periods of relative inactivity.

Depth of Focus

It’s not easy to predict when the tog will be “out to lunch” and when they will be home on the shallow water spots, but I have found that beautiful, sunny days with light winds and a rising barometer tend not to be conducive to good catches. Conversely, unsettled days with an approaching cold front, a falling barometer, and a stiff southerly wind often keep the fish at home and hungry for a free crab meal offering.

For tog inhabiting structures in the 15- to 30-foot depths, it’s common for them to leave their homes around the times of high tide to forage in the intertidal zone, so consequently, it can often be better to try and fish such places near low tide. This pattern breaks down when water temps drop below about 55 degrees. It is at that point that tog begin to avoid foraging in the shallows altogether as they begin to migrate to deeper water.

In deeper locations with swift currents, the tautog will often follow yet another pattern, spending much of its time inactive, hunkered down in rocky homes to conserve energy. During times of slack tide they emerge to feed locally, in and about the structures on which they live, unlike the far-roaming fish found in the shallows. It is during these brief periods of activity that the larger fish are most likely to take a baited hook. The prudent togger will schedule trips around these magic times.

If there is one generalization I could make about fall tog with regards to depth, it’s that they favor foraging in shallow water over deep (shallow meaning less than 20 feet), and that anglers should try to stay near good shallow water hunting grounds for as long as the water temps will allow. At least, this is what I’ve observed in my home waters of Long Island Sound. It makes sense, since structures in shallow waters tend to contain the greatest density per square yard of the prey organisms preferred by tog. Some veteran ‘tog anglers have also speculated that the abundance of Asian shore crabs in recent years has altered the feeding behavior of tautog, causing them to frequent the shallows more than they had in the past.

For me, the most exciting revelation made possible from underwater video came from witnessing how tog react to a bait, and what motivates them to eat it. Anyone who has ever fished for tog is familiar with the feel of how they bite: a series of small pecks and nibbles, followed by a sharp tug, signaling the time to set the hook. The commonly held interpretation of what is happening under the surface is that the initial pecks are caused by a fish working on your bait with its front incisors, and the thump, or tug, happens as the tog finally commits and passes the bait to its rear pharangeal “crusher” teeth. This scenario has been described similarly in countless blackfish articles over the years.

However, what I’ve actually observed happening is something quite different, and reveals a definite pecking order among tog. In fact, it seems the big whitechins “rule” the structures they call home.

Nibbles & Pecks

When your bait hits the bottom on a lively piece of structure, it’s immediately set upon by a swarm of small blackfish and bergalls, sometimes numbering in the dozens. It’s these fish that cause the small pecks and nibbles that are felt at the other end of the line. Nearby, your prize, the keeper-sized tog, may be watching this scene unfold from its lair. If you’re lucky, the greedy big fish will ambush the scene, scattering the small fry out of the way before totally engulfing the entire bait in an instant. The tog’s next move is to dart back into the structure with its booty. It’s at this moment that the sharp tug is often felt.

The whole process of a large tog approaching, attacking and moving off with the bait is over within a few seconds. Not once have I ever witnessed a sizeable tog nibbling or behaving in any way tentatively towards a bait. They are motivated partly by hunger, but also very much by competition and wanting to assert dominance over their smaller brethren. Finally, I’ve seen nothing to suggest a tog cares the slightest bit about what kind of hook, jig, or line is used to present a bait. It is the crab, and only the crab that interests him. In fact, the only way I’ve ever seen a large tog react to my leader is to annoyingly bump it out of the way with its nose in order to devour a bait. Yet, it’s quite probable there may be certain situations where your visual presentation could play a role in success.

For many years I had always been careful about keeping my presentation motionless on the bottom so as not to spook the supposedly shy, jittery tog. Again, I got a surprise when I captured their behavior on camera. Keeping the bait still seemed to encourage the little guys to come and chew, but when I moved the bait around just to try and feel for the bottom, the larger tog often became interested and approached, sometimes chasing the bait aggressively. This past season I experimented by casting a baited blackfish jig over boulders in shallow water and retrieving it so that it skimmed just above the structure in full view of any togs below. Occasionally, I’d let the jig drop to the bottom. This technique resulted in quite a few strikes from decent-sized fish, often as soon as the jig came to rest.

In case I’ve left any doubt in the reader’s mind as to the aggressiveness of a hungry tautog, I’ll leave you with this. It happened during my very first day of attempting to shoot underwater video of tautog. About 20 minutes into the session my bait suddenly got slammed by a big fish. I made progress trying to bring up the beast for about three seconds before the fish got serious and dove for the bottom. There was nothing I could do to stop it, and when my line touched the structure it parted instantly. I quickly reeled in the camera and, without missing a beat, picked up my jigging stick, which I had already pre-baited with a crab. I sent down the new offering in the same exact spot where I had lost the big one. Before the jig even hit bottom I was into a second big fish.

Using a more appropriate setup and not having my camera rig tied on, I was able to wrest this fish up out of the structure and to the net. When I went to unhook the fish I was stunned to see that it had not only my jig in its mouth, but also the hook and frayed leader from my camera rig! The fish had been hooked once, fought to break free, and was not even rattled enough to refuse a second offering not three minutes later!

The fish measured 25 inches, weighed 8.5 pounds, and was my personal best from a kayak. After posing for a few selfies, I released the big female to pass on its good genes.